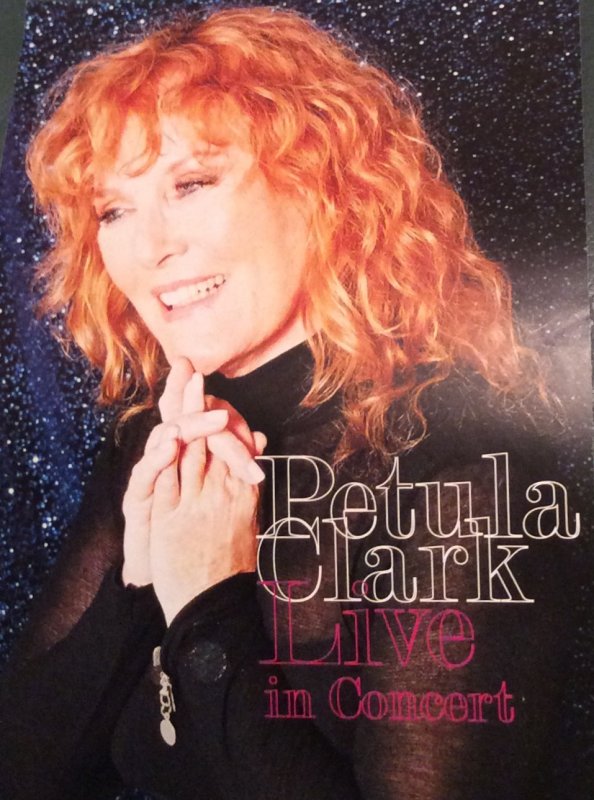

LIVE - IN CONCERT

THE MILLENNIUM

2000

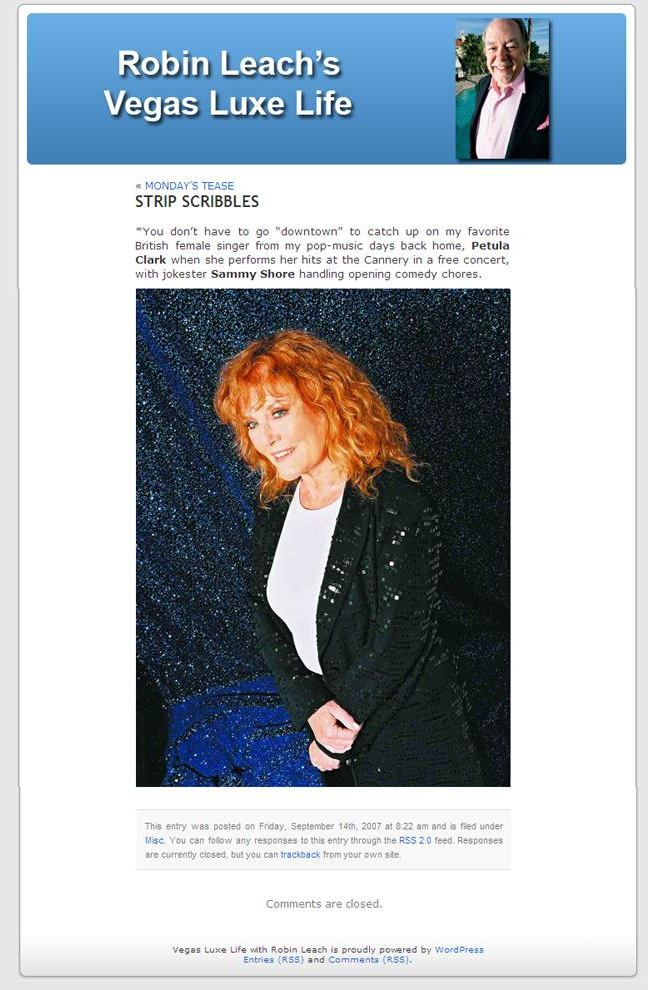

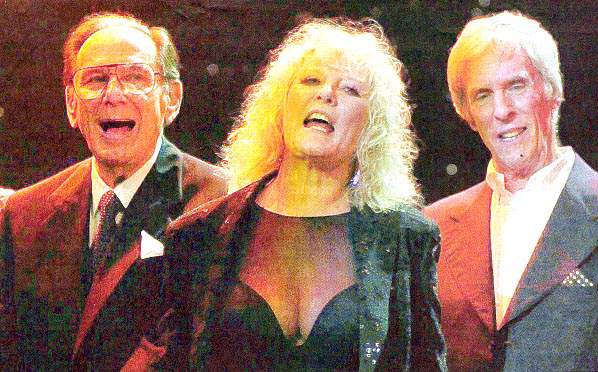

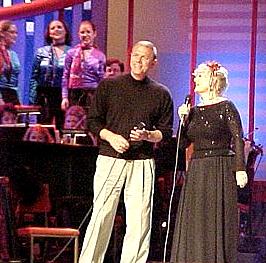

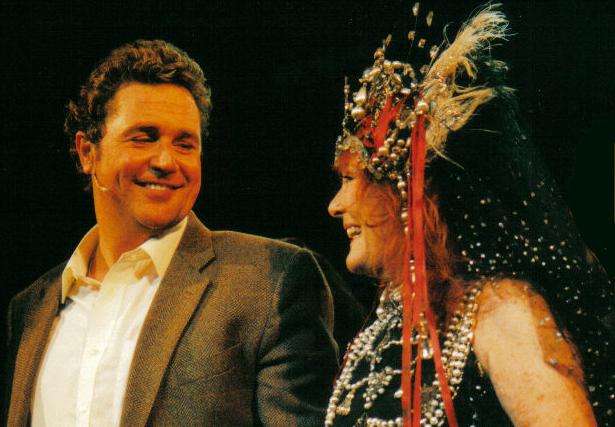

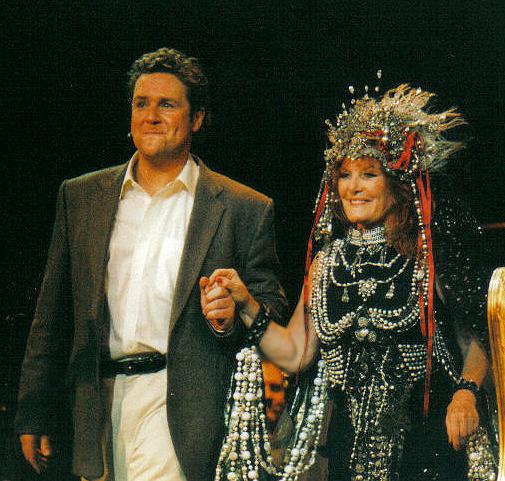

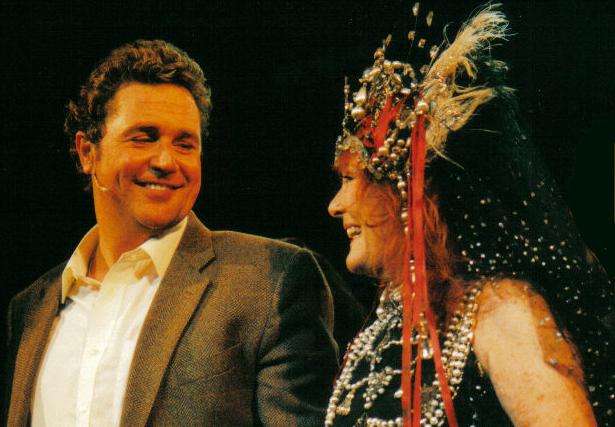

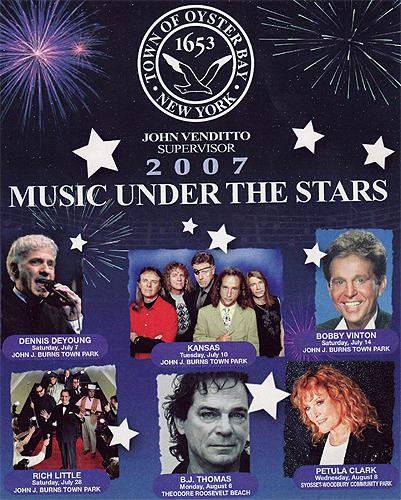

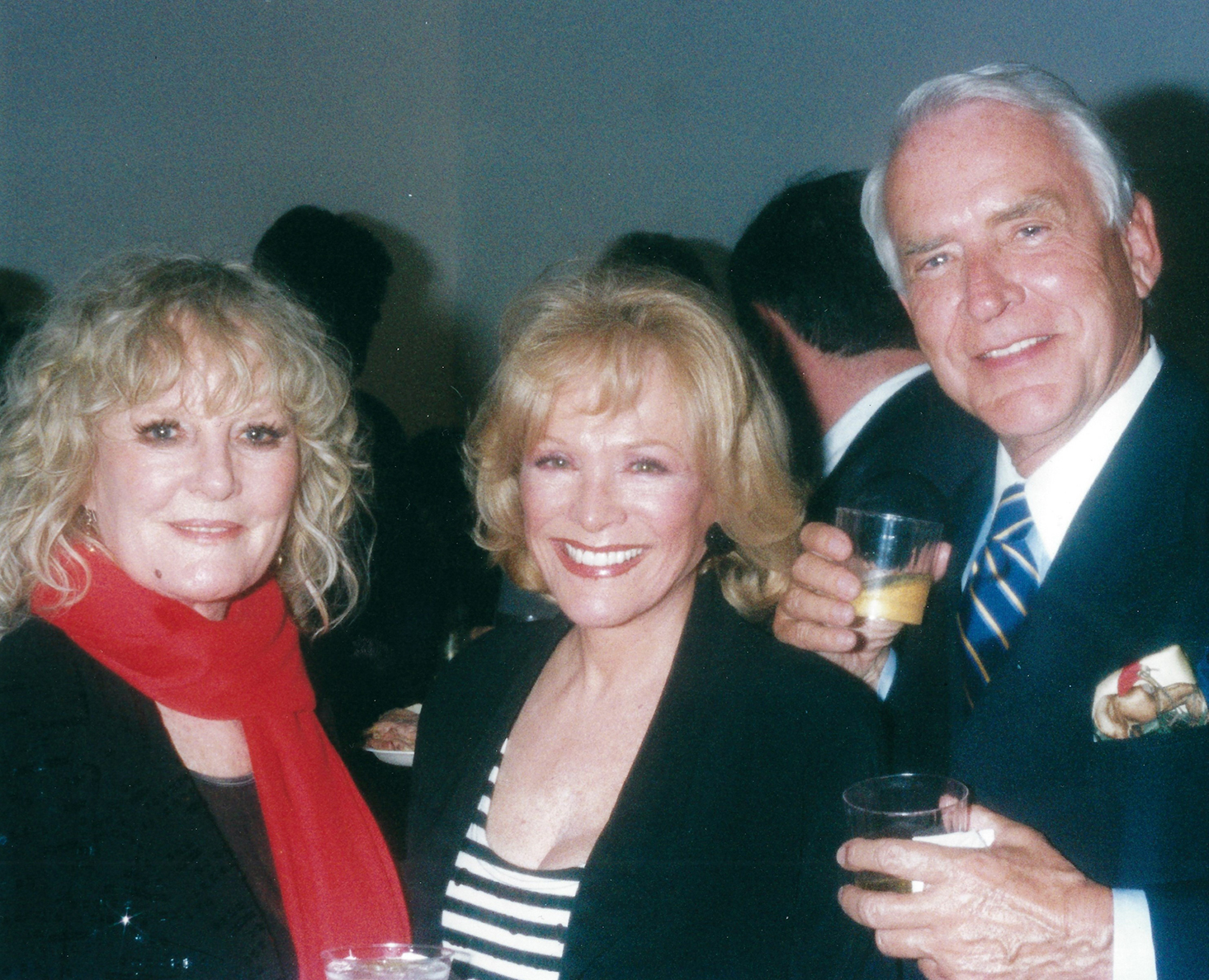

Hal David, Petula Clark, Burt Bacharach singing "What the World Needs Now" (London Evening Standard photo)

Royal Albert Hall Review

3rd July 2000

EVERY ONE A PET SONG

You wouldn't think that a Nordoff-Robbins charity event in honour of the celebrated songwriting duo of Bacharach and David could be cause for mild controversy, but there was an element of that here. On one hand the fans who wanted to singalong to non-stop pop classics; on the other, those who wanted to admire the artistry in studied awe.

In between, were a few aggrieved punters who demanded to know where Bacharach and David actually were. Eventually Burt would appear to play piano for Elvis Costello and Dionne Warwick, while Hal emerged from the wings for bows and speeches.

The first half was dominated by Petula Clark and Sasha Distel, genuine stars both. Pet's status as our most successful female pop star was cemented by the gravitas she applied to A House is Not a Home. Sacha's Gallic charms were self-evident in the gorgeous Raindrops keep fallin' on my head. The second half began with a wobbly Leo Sayer rendition of (There's) Always Something There to Remind Me. It picked up steam once Costello added an element of class to I Just Don't Know What to Do with Myself as Burt tinkled the ivories. Elvis slipped into Dionne and the night exploded with the urban classics Walk on By, Say a Little Prayer, San Jose and Anyone who Had a Heart, a quartet of pop standards that give the genre a good name.

3rd July 2000

EVERY ONE A PET SONG

You wouldn't think that a Nordoff-Robbins charity event in honour of the celebrated songwriting duo of Bacharach and David could be cause for mild controversy, but there was an element of that here. On one hand the fans who wanted to singalong to non-stop pop classics; on the other, those who wanted to admire the artistry in studied awe.

In between, were a few aggrieved punters who demanded to know where Bacharach and David actually were. Eventually Burt would appear to play piano for Elvis Costello and Dionne Warwick, while Hal emerged from the wings for bows and speeches.

The first half was dominated by Petula Clark and Sasha Distel, genuine stars both. Pet's status as our most successful female pop star was cemented by the gravitas she applied to A House is Not a Home. Sacha's Gallic charms were self-evident in the gorgeous Raindrops keep fallin' on my head. The second half began with a wobbly Leo Sayer rendition of (There's) Always Something There to Remind Me. It picked up steam once Costello added an element of class to I Just Don't Know What to Do with Myself as Burt tinkled the ivories. Elvis slipped into Dionne and the night exploded with the urban classics Walk on By, Say a Little Prayer, San Jose and Anyone who Had a Heart, a quartet of pop standards that give the genre a good name.

Albert Hall ~ Bacharach and David Gala Tribute

3 July, 2000

by Paul Sexton

Nordoff-Robbins Music Therapy is rightly revered as a source of inspiration to autistic and otherwise disabled children, but as part of its 25th anniversary on Friday, the charity raised further funds while providing another kind of public service. Tribute concerts often take place to a camouflaged backdrop of commercial motivation, but good causes have rarely sounded as good or been served as elegantly as at this gala celebration of two cornerstones of the popular song, the composer Burt Bacharach and the lyricist Hal David.

Such tribute occasions customarily produce a handful of relevant luminaries and a boot-sale of extras, but with one or two mildly windy hiccups, this one exuded both relevance and dignity. Setting it on a London stage was also entirely apposite, since both writers have acknowledged the important role played by British artists and audiences in broadening their appeal, as their tunes were amplified by Tom Jones, Sandie Shaw, Dusty Springfield and others.

A bill featuring Kenny Lynch, Sacha Distel, Linda Lewis and Edwin Starr might sound as though it belongs at the Palladium or on a where-are-they-now package tour, but each contributed to the momentum of the testimonial, as did Lucie Silvas, Lynden David Hall, Paul Carrack and the remarkably composed newcomer Sumudu Jayatilaka. Petula Clark closed the first half with an initially cautious but ultimately victorious presentation that included "Close To You" and one of David's most handsomely expressive lyrics, "A House Is Not a Home."

After the interval it fell to Bacharach's most recent collaborator, Elvis Costello, to introduce him and use his piano accompaniment for "I Just Don't Know What To Do With Myself." Finally Bacharach and David's keynote interpreter Dionne Warwick emerged, going some way to redeeming a lacklustre performance at Hammersmith two nights earlier, and it was time to say a little prayer for the creators of a catalogue that only grows more mighty as contemporary songwriting values grow more slovenly.

3 July, 2000

by Paul Sexton

Nordoff-Robbins Music Therapy is rightly revered as a source of inspiration to autistic and otherwise disabled children, but as part of its 25th anniversary on Friday, the charity raised further funds while providing another kind of public service. Tribute concerts often take place to a camouflaged backdrop of commercial motivation, but good causes have rarely sounded as good or been served as elegantly as at this gala celebration of two cornerstones of the popular song, the composer Burt Bacharach and the lyricist Hal David.

Such tribute occasions customarily produce a handful of relevant luminaries and a boot-sale of extras, but with one or two mildly windy hiccups, this one exuded both relevance and dignity. Setting it on a London stage was also entirely apposite, since both writers have acknowledged the important role played by British artists and audiences in broadening their appeal, as their tunes were amplified by Tom Jones, Sandie Shaw, Dusty Springfield and others.

A bill featuring Kenny Lynch, Sacha Distel, Linda Lewis and Edwin Starr might sound as though it belongs at the Palladium or on a where-are-they-now package tour, but each contributed to the momentum of the testimonial, as did Lucie Silvas, Lynden David Hall, Paul Carrack and the remarkably composed newcomer Sumudu Jayatilaka. Petula Clark closed the first half with an initially cautious but ultimately victorious presentation that included "Close To You" and one of David's most handsomely expressive lyrics, "A House Is Not a Home."

After the interval it fell to Bacharach's most recent collaborator, Elvis Costello, to introduce him and use his piano accompaniment for "I Just Don't Know What To Do With Myself." Finally Bacharach and David's keynote interpreter Dionne Warwick emerged, going some way to redeeming a lacklustre performance at Hammersmith two nights earlier, and it was time to say a little prayer for the creators of a catalogue that only grows more mighty as contemporary songwriting values grow more slovenly.

Songs Performed

Part I

Part I

- Here We Are

- Color My World

- I'm Not Afraid

- World War II

- Un Enfant

- Look to the Rainbow / How are Things in Glocca Morra

- You and I

- Que Fais tu la, Petula

- Je Me Sens Bien

- La Gadoue

- Chariot

- Don't Sleep in the Subway

- Celebrate

Part II

- If I Had You

- Just You, Just Me

- Coeur Blessé

- I Never Do Anything Twice

- 60s medley:

Downtown/Sign of the Times I Know a Place/Round Every Corner The Other Man's Grass is Always Greener Kiss Me Goodbye/This is My Song My Love/Downtown - Tell Me It's Not True

- With One Look

- Theatre poem

- Vivre

- Here for You

Encores:

- I Couldn't Live Without Your Love

- Tout le Monde Veut Aller Au Ciel, Mais Personne ne Veut Mourir

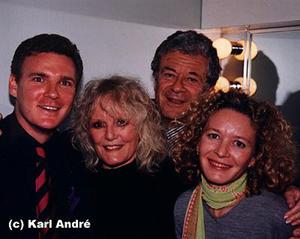

Above photos © Karl André

Above photos © Karl André

Sylvain Cormier

Sylvain CormierNovember 4-10, 2000

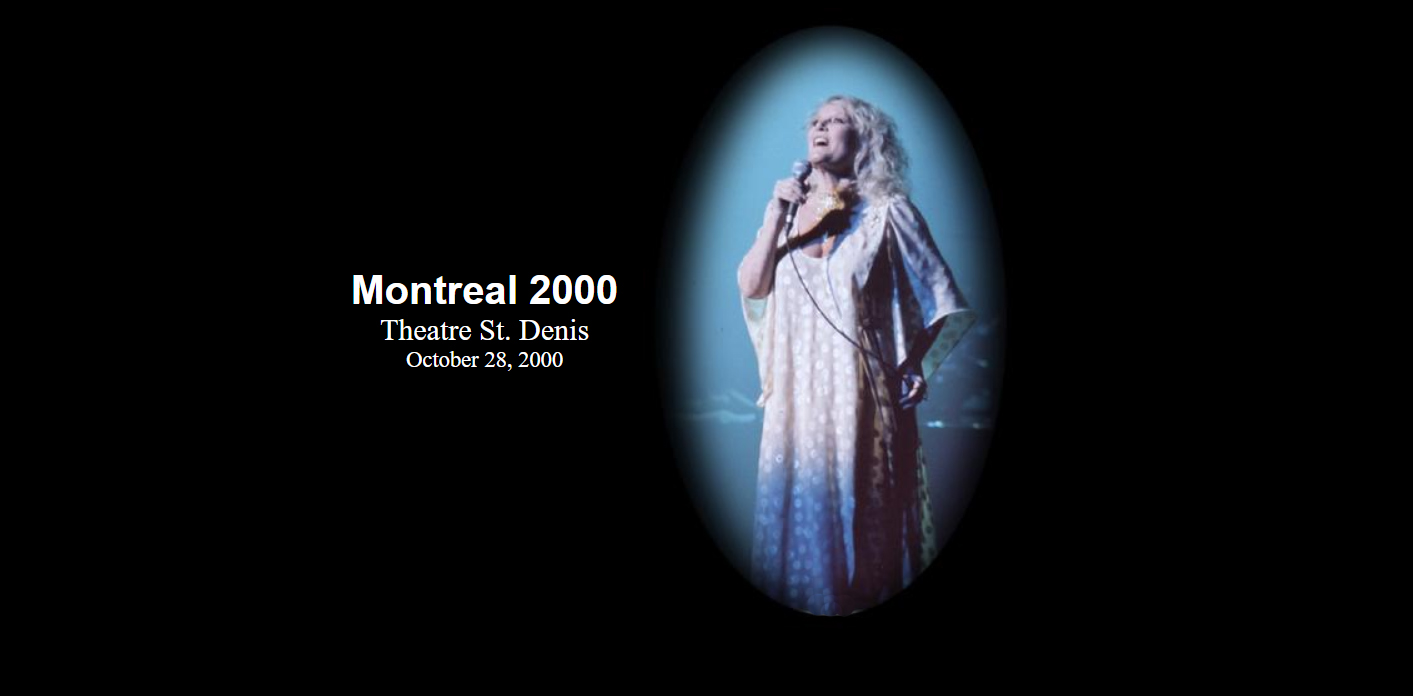

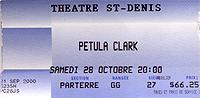

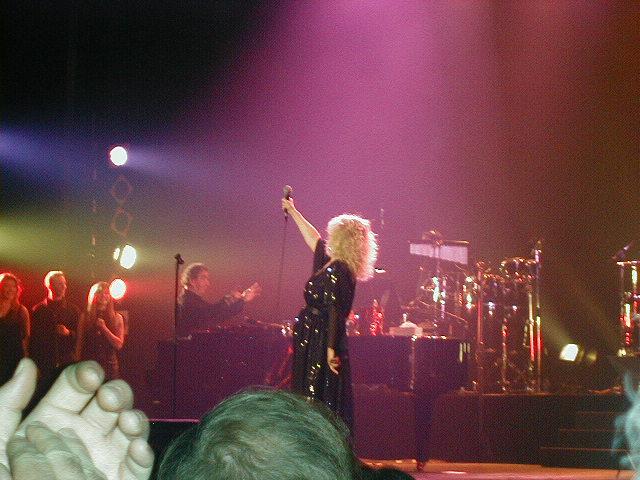

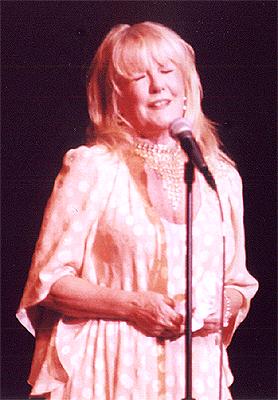

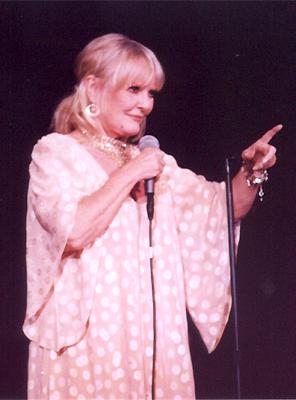

AN EXQUISITE EVENING

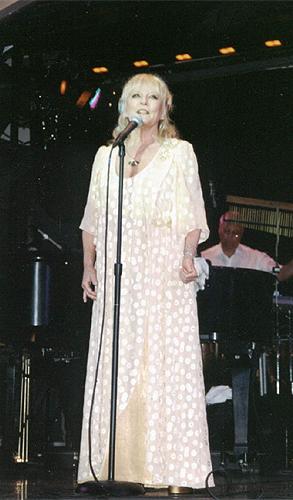

The operation was a risk. Preparing a show in a few weeks, with musicians that you do not know very well without having a chance to try it out, is a big thing. However, last Saturday at Theatre St-Denis, Petula Clark succeeded this tour-de-force in offering the audience a fantastic performance. We all wanted to hear her and this lady was happy to please us all. She told us parts of her life, some of it in English and some of it in French. She sang some thirty songs that she's been performing for almost six decades. She has real class, a voice that never seems to be out of breath and songs that she feels from inside. A few highlights of the show were when she performed: I'm Not Afraid, Don't Sleep in the Subway, Downtown, Tell Me It's not True, and Vivre from Notre Dame de Paris. Scott Price did an excellent job at conducting this first class band. An exquisite evening. A priviledged moment.

~J.-F. Brassard (Translation by Daniel Bédard)

Photos © Clément Brilliant

Photos © Clément Brilliant

Sylvain Cormier

Sylvain CormierLe lundi 30 octobre 2000

TOUJOURS PETULA

Charmé? Je l'étais depuis l'entrevue. Fan? Je le suis depuis l'enfance, capable de chanter Don't Sleep In The Subway sur demande. Mais ravi, totalement heureux d'avoir vu et entendu Petula Clark sur scène? Seulement depuis samedi soir au Saint-Denis. Comme tout l'auditoire, qui a constat&egrav; en même temps que moi l'évidence: l'interprète est grandissime, la femme a la soixantaine resplendissante, et l'individu est irrèsistiblement chouette.

Petula? Simplicité, gràce and greatness au rendez-vous. Intelligence, sensibilité et drôlerie itou. And common sense en plus. C'est voulu, les mots en anglais. C'est pour faire comme elle. Faut-il rappeler que Petula Clark fit carrière dans les deux langues officielles de chez nous, l'anglais et le français, qu'elle fut d'abord l'enfant chèrie du Royaume-Uni, puis la darling yêyê de la France, avant de devenir la mondiale Petula de Downtown au milieu des groovy sixties? Elle aurait pu nous fourguer un spectacle à l'américaine, surtout après un quart de siècle d'absence de la scène québêcoise, mais pas du tout: la presque totalité des chansons - même les récentes - étaient fully bilingual dans le texte. Jusqu'aux prèsentations qui bênêficiaient du même me gênêreux traitement, sans qu'on n'ait jamais l'impression de doublage instantanê. She's a natural, quoi.

C'est le mot: Petula Clark est une sacrêe nature. Parfaitement à l'aise sur scène, drôlement dê gourdie et carrê ment indê montable, fû t-ce par une robe mal attachê e qui l'abandonne en cours de pot-pourri: la Galloise fit un p'tit signe à ; l'habilleuse, laquelle arrangea l'affaire devant nous. "One of those funny things about the theater", comme dira la chanteuse dans un poè ;me de son cru sur le monde des planches.

De fait, tout le spectacle êtait prêsentê comme un musical qui aurait eu Petula Clark pour sujet. Difficile d'imaginer plus habile faç on de mettre en contexte plus de soixante ans de carrière (elle chantait pour les troupes "during World War II"): toutes les êtapes de son parcours devenaient autant de tableaux, oò l'êquilibre entre anecdotes et chansons &etait idêal. Sêquence retrouvailles (Here We Are, Colour My World), portion fillette (enregistrement tout crêpitant de Petula à la BBC Overseas Service, mis en perspective par Un enfant, (de Brel), medley cinêma (extraits de Finian's Rainbow et Goodbye Mr. Chips), ê ;pisode yê ;yê ; (Que fais-tu là ;, Petula?, La Gadoue, Chariot, Coeur blessé ;), voyage sixties (Sign Of The Times, I Know A Place, This Is My Song, Downtown), le spectacle n'oubliait à peu près rien d'essentiel, sans négliger le pré ;sent: les échantillons des comédies musicales Blood Brothers et Sunset Boulevard, rêcents ajouts au curriculum, ont au moins autant plu que les tubes.

Même sa version de Vivre (oui, celle de Notre-Dame de Paris) n'aura pas déparé l'ensemble: j'en apprèciais Plamondon. Jusqu'à cet orchestre tout-Quêbecois dont elle connaissait chaque prénom, Petula Clark aura été à l'impossible hauteur de sa légende, se montrant précisèment à dimension humaine: accessible, charnelle et entière. Quite a dame, je dois dire.

Sylvain Cormier

Sylvain CormierLe lundi 30 octobre 2000

ALWAYS PETULA

Charmed? I was since the interview. A Fan? I am since childhood, and am able to sing "Don't Sleep In The Subway" on request. But delighted , and completely happy to have seen and heard Petula Clark on stage? Only since Saturday night at the Thêātre St-Denis. Like everyone in the audience who noticed at the same time as me the evidence: the performer is tremendous, woman in her sixties is dazzling, and the individual is irresistibly cute.

Petula? Where simplicity, grace and greatness meet. Likewise for intelligence, sensitivity and funniness. And common sense in addition. These English words are wanted . (N.B. In the original French text, words are purposely left in English) It's to do like her. Must one recall that Petula Clark made her career in both of our (in Canada) official languages, English and French, that she was the darling child of the United Kingdom, then the darling yêyê (60's pop star) of France, before becoming the world-renowned Petula of "Downtown" in the middle of the groovy sixties?

She could have unloaded an American style show , especially after a quarter century's absence from the Quêbec stage, but not at all: almost all of the songs-even the recent ones' lyrics were completely bilingual. Up to the introductions which benefited from the same generous treatment without our ever having the impression of a simultaneous translation. She's a natural at that.

That's the word: Petula Clark is a sacred nature. Perfectly at ease on stage, unusually bright, and bluntly can't be taken down, either by a badly tied dress which comes apart in the middle of a medley: the Welsh woman made a small sign to the dresser who adjusted the dress in front of the audience. "One of those funny things about the theater", says the singer in a poem about her belief in the world of the stage.

In fact, the entire show was presented as a musical which would have had Petula Clark as its subject. It's hard to imagine a more skillful way in which to put into context more than sixty years of a career (she sang for the troops "during World War ll.": all the steps of her journey became as much a scene (in a play) , where the balance between stories and songs was ideal.

A "reunion" sequence(Here We Are, Colour My World), little girl segment(a crackling sounding recording of Petula at the BBC Overseas Service, put in perspective by "Un Enfant" written by Brel), a cinema (motion picture )medley (excerpts from Finian's Rainbow and Goodbye Mr. Chips), yêyê sequence (Que fais-tu là, Petula?, La Gadoue, Chariot, Coeur blessé, sixties trip (Sign Of The Times, I Know A Place, This Is My Song, Downtown), almost nothing essential was forgotten in the show, without neglecting the present: the samples from the plays Blood Brothers & Sunset Boulevard, recent additions to the repertoire, pleased as much as the hits.

Even her version of Vivre (yes, the one from Notre-Dame de Paris) would not have spoiled the whole: I appreciated Plamondon.(Quebecois composer who wrote "Vivre"), up to the orchestra-- made up of Quebecoise of whom Petula knew each musician's first name. Petula Clark would have been at the impossible summit of her legend, showing of herself a human side: accessible, passionate and whole. Quite a dame, I must say.

[French translation courtesy of Jean Thivierge]

Above photos © Pat Fox

By Martin Siberok

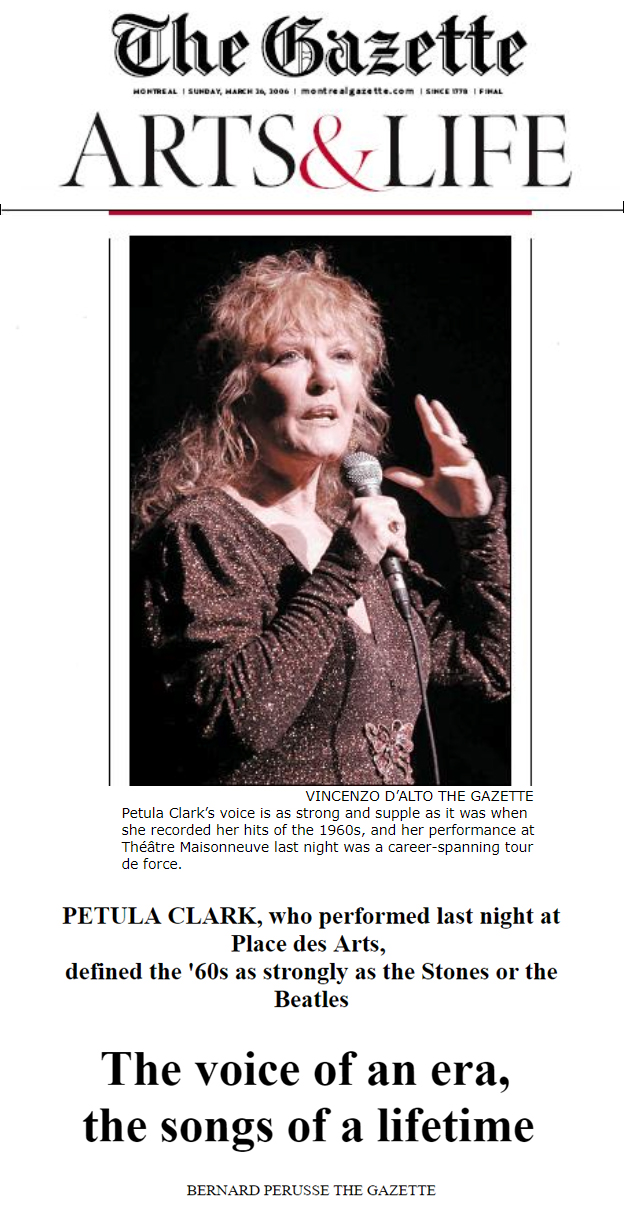

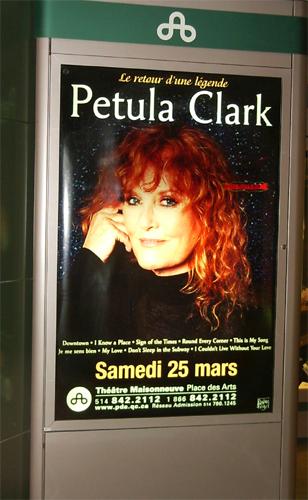

By Martin Siberok Bilingual Clark wows Montreal Switching between French and English, the singer displayed an easy charm and a strong buoyant voice.

Petula Clark would make a perfect Canadian - the fluently bilingual kind that Pierre Trudeau dreamed this country would produce. Switching effortlessly between French and English, Clark took over Théàtre St. Denis Saturday night. This was the only Canadian date on her North American tour, which picks up in California next month, and she was making the most of being in Montreal.

The last time Clark played this city was in 1976. It was a period of heightened political tension, and the singer's determination to switch between English and French was not well received by some fans and critics. Her return almost a quarter of a century later was much more welcoming, signalling a markedly different social reality in Quebec. Clark is an international star, and the audience proved it can now appreciate a celebrity of her stature without feeling threatened by her easy bilingualism.

The former child star -- who turns 68 on Nov. 15 -- is clearly at home on any stage. Acting the gracious host, Clark guided her fans through a Vegas-style evening dedicated to her 60-year career. From her early days entertaining the Allied troops during the Second World War, to being an "Anglais" star in France, to the pop-filled sixties, to her Hollywood films and Broadway musicals, Clark has always revealed herself as a consummate performer. Over the years, she has sold nearly 70 million records in four languages -- English, French, Italian and German -- and is still the most successful female singer in British chart history.

So it was rewarding to see how well her voice has survived the years. Strong and buoyant, it showed no signs of faltering as Clark tackled a variety of styles -- jazz, pop, British music-hall numbers, French chansons and Broadway tunes. And with most of her songs clocking in at the three-minute mark, Clark was able to cover a lot of territory in a scant two hours.

Her pop days were rolled into a sixties medley, with snippets of I Know A Place, A Sign of the Times and My Love, and culminating in an extended version of Downtown, thanks to additional French verses. The seven-song medley served as a worthy tribute to the singer's fruitful collaboration with songwriter Tony Hatch -- Britain's answer to Burt Bacharach -- whose elegant arrangements were some of the best of that decade.

Throughout her career, Clark has had many admirers, including John Lennon, Michael Jackson and Sheryl Crow, as well as Canadian piano virtuoso Glenn Gould, who said that her work with Hatch was better than the Beatles. Highlights of the evening's well-paced repertoire were a stunning rendition of Don't Sleep in the Subway, with its rich Beach Boy-esque harmonies, a rousing Tell Me It's Not True from the Blood Brothers musical, and I Am Not Afraid, a candid testimonial about being forever in the public eye.

As Clark confessed, "Growing up in front of millions wasn't fun." Despite building a solid career in Britain in the forties as a Shirley Temple equivalent, Clark felt stifled by fans who wouldn't allow her to grow up.

It was only when she moved to France in the late 1950s, and started performing sophisticated French pop songs written by Jacques Brel and Serge Gainsbourg, that she was finally able to shake her image of the eternal adolescent.

For the evening's largely francophone crowd, Clark sang many of her French hits, such as Que fais-tu la Petula? and Chariot, as well as adding French lyrics to several of her English songs. As a treat for her Montreal fans, she covered a stirring Vivre, taken from the Notre-Dame de Paris musical written by local hero Luc Plamondon.

When the show concluded and Clark basked in the limelight, several male fans rushed the stage to offer her bouquets of red roses. It was a fitting gesture for a seasoned performer who proved beyond a doubt that she deserves all the accolades she has received.

The West Island Suburban

By Craig McKeeAn unforgettable night with Petula

Every once in a while a performer comes along who doesn't get the credit she deserves until you see her live.

For me, that performer is Petula Clark.

The full house that was on hand at the St.Denis Theatre on Saturday night was taken on a journey through the life and career of the British superstar --- a career that has lasted more than 50 years.

All but two musicians in her nine-piece band, as well as her four backup singers, were recruited locally, but you wouldn't know they hadn't been together for years. When Petula broke into our consciousness with Downtown in the mid-1960s, she seemed to be made for the time. The songs and her voice seemed quintessentially British. I saw her for the first time when the Ed Sullivan Show taped at Expo 67 in Montreal. And even as an eight-year-old I knew that I loved that music.

When I found out she was coming back to Montreal I was anxious to hear the old hits again. And while I loved hearing them all as much as I could have hoped, I was pleasantly thrilled at how much I loved the more unfamiliar material that she shared with the audience. It really gave me the opportunity to appreciate --- more than I perhaps had before --- just how great a performer Clark is. At 68, she looks great and her voice, if anything, is better than ever. And her stage persona is so down to earth and charmingly vulnerable that you can't help but like her.

Clark moved easily between English and French, both in her descriptions of her career and life and in her songs. She performed a variety of French songs, some from her past as a recording star in France. She sang Un Enfant by Jacques Brel, her early hit Que Fais-tu là Petula?, Je Me Sens Bien, Coeur Blessé as well as crowd favourite Tout le Monde... in her encore.

She also threw in French verses in some of her best known English hits. For those who prefer that part of her repertoire, she didn't leave anything out. She gave us wonderful renditions of Tony Hatch compositions like Downtown, Don't Sleep in the Subway, I Know a Place, I Couldn't Live Without Your Love, Colour My World, Sign of the Times, The Other Man's Grass is Always Greener, and My Love. She also sang the Charlie Chaplin penned This is My Song.

While I went to the concert knowing how much I loved these hits, I came away with a vastly increased respect for Petula's talent as a singer. Her performances of songs from her Broadway career like Sunset Boulevard, Blood Brothers, and from her films Finian's Rainbow and Goodbye Mr. Chips really showed her considerable abilities as a vocalist. In one touching moment, she sang about World War II while a recording of her singing on the BBC at the age of eight played in the background.

All in all, it was a wonderful night that I'll never forget. We can only hope she comes back very soon. Don't miss her if she does.

(Transcribed by Charles-André Ferron)>

Above photos ©Laurie Parsons Zenobio

Photo by Jim Noll

All photos ©Karl André, except as noted.

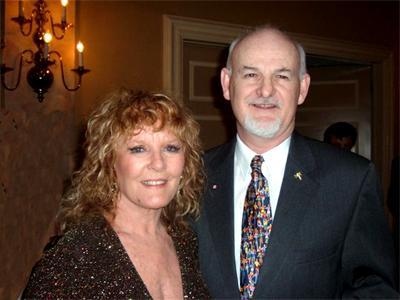

Backstage - Patrick, Petula, Claude & Kate

Backstage - Patrick, Petula, Claude & Kate

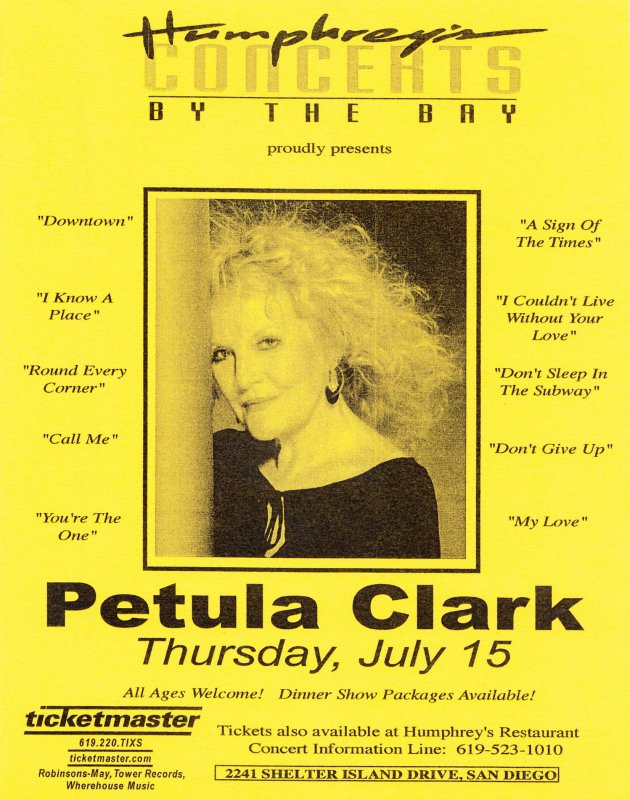

San Diego Civic Theatre

San Diego, California, USA

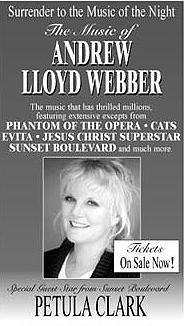

THE MUSIC OF ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER

Starring: PETULA CLARK.

Singers: Jason Burke, Tara Lynn Cotty, Michele Marin, Fabiola Reis, Nick Sattinger, Kristen R. Butcher, Erin Davie, Neil Michaels, Mark Rinzel, Tangena Church, Stephanie Garza, Michael Pesce, Brian Charles Rooney, Christopher Sloan.

San Diego Civic Theatre

San Diego, California, USA

THE MUSIC OF ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER

Starring: PETULA CLARK.

Singers: Jason Burke, Tara Lynn Cotty, Michele Marin, Fabiola Reis, Nick Sattinger, Kristen R. Butcher, Erin Davie, Neil Michaels, Mark Rinzel, Tangena Church, Stephanie Garza, Michael Pesce, Brian Charles Rooney, Christopher Sloan.

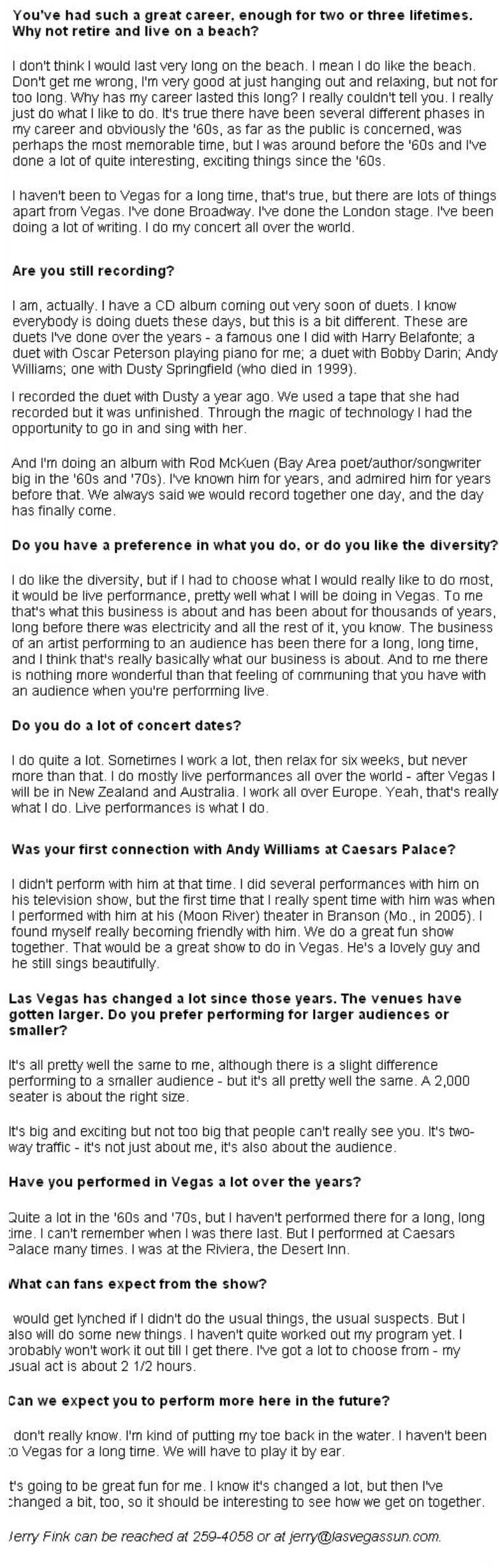

Sign of the times: 'Music of Andrew Lloyd Webber' gets a boost from Petula Clark

Sign of the times: 'Music of Andrew Lloyd Webber' gets a boost from Petula ClarkBy Anne Marie Welsh

Union-Tribune Theater Critic

November 2, 2000

The speaker sounds young, vital, full of humor, like the ageless singer. "One way I'm different" says Petula Clark, "is that most of the girls who played Norma Desmond kept some of those elaborate (Bob Mackay) costumes. That's the last thing I wanted. To show up at some party looking like that self-absorbed, delusional old star."

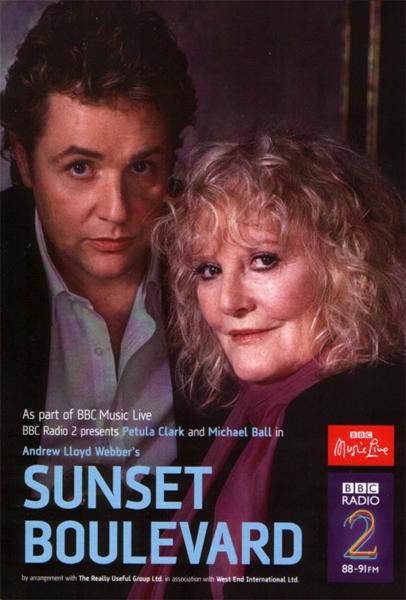

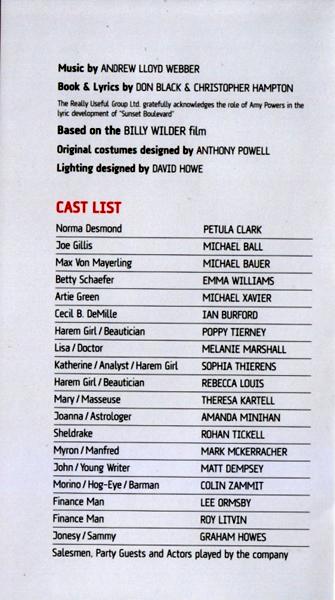

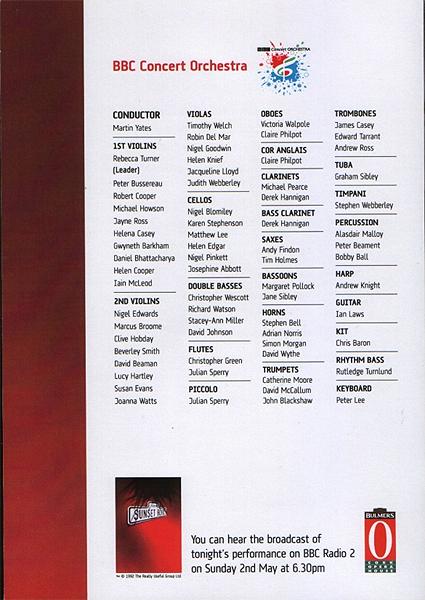

The British pop star, who turns 68 next month, charmed San Diego audiences last year by lifting the heavy heart of Andrew Lloyd Webber's lugubrious "Sunset Boulevard" with her canny performance as that fading film star, Norma. Clark returns Tuesday as herself in an evening of music by Sir Andrew, backed by the 28-piece Philharmonica Orchestra and a dozen singing, dancing performers.

Clark is in Montreal as we speak, recovering from the excitement of a show she premiered the night before. "I feel as if I'd been kicked by a donkey," she says. "All that excitement and then the big letdown."

As Clark (aka Mrs. Claude Wolff) describes that autobiographical show, tentatively titled "Sign of the Times" and sung half in English, half in French, you soon realize that thinking of her as a chart-topping British pop star from the '60s ("Don't Sleep in the Subway," "Downtown," "My Love") is like saying Baryshnikov is a good ballet dancer. It doesn't cover much of the territory.

The singing Welsh

Born in Surrey in 1932 of an English father and Welsh mother ("all the Welsh are singers"), Clark says, "I'm not nostalgic particularly, though I do go back to my childhood in the new show. I've written a special piece, a kind of half poem and half song, like a tone poem about what it felt like to be a child during the war."

Before her U.S. success, which began with the Grammy-winning "Downtown" in 1964, she says, "I had this career in France for many years. I married a Frenchman (Wolff). So (in Montreal) they love the new show, which is partly in French. Of course, they have an agenda here," she says, referring to Quebec separatists."

She and the Frenchman have three children (Kate, Barbara and Patrick, all grown) and a 4-year old grandchild, Sebastian, who's bilingual. Already he's a singer who "enchants everyone who hears him," Clark says.

Life before and after "Downtown"

"I had a life before the '60s and a life since," she says, without pointing directly to the many movies ("Finian's Rainbow") and stage appearances ("The Sound of Music") interspersed with the recordings that have sold more than 30 million worldwide.

"I never say, 'They don't write 'em like they used to.' I'm enjoying my life and career now more than ever."

Though Glenn Close warned Clark she'd be in a looney bin if she stayed in "Sunset" longer than eight months, Clark has performed the show more often than Close or any of the others (Patti LuPone, Betty Buckley, Elaine Paige) who inhabited the fading fancies of Norma D. "I was ready to be myself again onstage," Clark says, explaining her return to concertizing.

The Lloyd Webber evening has been fashioned by director Arlene Phillips, employing tunes from early pieces, the megahits "Phantom of the Opera," and "Cats" and "Evita," and a more recent of the composer's works, "Whistle Down the Wind." Promotional material calls the show inspirational and unforgettable. And while many critics might find other, less laudatory words for the swelling anthems of the mighty populist Lloyd Webber, it's anybody's guess how his music will sound when Clark gets a hold of it.

Her wit, vulnerability and feminine sweetness, not to mention her unquenchable vitality, transformed "Sunset Boulevard" into something else again. Maybe next week, she'll personalize "Memory" or "Don't Cry for Me, Argentina" in the same way.

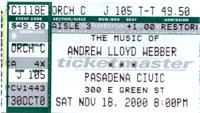

Pasadena Civic Auditorium

Pasadena, California, USA

THE MUSIC OF ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER

STARRING: PETULA CLARK.

Singers: Jason Burke, Tara Lynn Cotty, Michele Marin, Fabiola Reis, Nick Sattinger, Kristen R. Butcher, Erin Davie, Neil Michaels, Mark Rinzel, Tangena Church, Stephanie Garza, Michael Pesce, Brian Charles Rooney, Christopher Sloan.

Pasadena Civic Auditorium

Pasadena, California, USA

THE MUSIC OF ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER

STARRING: PETULA CLARK.

Singers: Jason Burke, Tara Lynn Cotty, Michele Marin, Fabiola Reis, Nick Sattinger, Kristen R. Butcher, Erin Davie, Neil Michaels, Mark Rinzel, Tangena Church, Stephanie Garza, Michael Pesce, Brian Charles Rooney, Christopher Sloan.

by Joel Hirschhorn

by Joel HirschhornReuters/Variety, November 16, 2000

"Lloyd Webber's Music Basks in Spotlight"

HOLLYWOOD -- "The Music of Andrew Lloyd Webber" showcases Lloyd Webber's music with simplicity and restraint.

Liberated from the weight of cats, chandeliers and roller skates, the melodies have more power than they ever did in swollen, spectacular settings. Arlene Phillips, director and choreographer, keeps the production simple and straightforward, making musicianship a priority, and she has chosen an ensemble of dynamic singers to interpret the material.

Special guest star Petula Clark enters the stage calmly and stays cool as she launches "I Don't Know How To Love Him." Her rendition is marked by thoughtful pauses and emotional intelligence, breaking the phrase "he's just... one more" in two, for example.

Clark is an unusual artist, much more so than generally recognized. She makes legit singing acceptable to the masses by minimizing vibrato and adding pop licks on "Don't Cry For Me Argentina," a prime example of her ability to bridge the Broadway and commercial music world.

The show kicks off with Mark Rinzel's rousing version of "Jesus Christ Superstar." Christopher Sloan, does "Close Every Door" from "Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat" and holds the audience spellbound with his strong, searching delivery.

"Starlight Express" is energetically dramatized by Nick Sattinger and Neil Michaels. Michaels then returns like a singing Elmer Gantry with his thunderous gospel rendition of "There's a Light at the End of the Tunnel," another "Starlight Express" number which proves memorable music can come from mediocre shows.

Inevitably, Clark gets to "Memory," the only tune of the evening that feels overly familiar -- it's more fun to watch Sattinger wail out "Mr. Mistoffelees" from "Cats." Toward the show's conclusion, Clark takes over as a star and offers heartfelt performances of "The Perfect Year" and "With One Look."

Brian W. Tidwell, music director and conductor, makes sure that his 28-piece orchestra, the Philharmonica Europa, never overwhelms the singers yet shines through every selection.

Presented by the Pasadena Civic Auditorium Foundation. Directed and choreographed by Arlene Phillips. Lighting, Vivien Leone; musical director, Brian W. Tidwell; sound design, Mark Norfolk.

The Music of Andrew Lloyd Webber (The Pasadena Civic; 3,000 seats; $55 top). Starring: Petula Clark; singers, Jason Burke, Tara Lynn Cotty, Michele Marin, Fabiola Reis, Nick Sattinger, Kristen R. Butcher, Erin Davie, Neil Michaels, Mark Rinzel, Tangena Church, Stephanie Garza, Michael Pesce, Brian Charles Rooney, Christopher Sloan. Opened and reviewed Nov. 14, 2000; closes Nov. 19.

HOLLYWOOD -- "The Music of Andrew Lloyd Webber" showcases Lloyd Webber's music with simplicity and restraint.

Liberated from the weight of cats, chandeliers and roller skates, the melodies have more power than they ever did in swollen, spectacular settings. Arlene Phillips, director and choreographer, keeps the production simple and straightforward, making musicianship a priority, and she has chosen an ensemble of dynamic singers to interpret the material.

Special guest star Petula Clark enters the stage calmly and stays cool as she launches "I Don't Know How To Love Him." Her rendition is marked by thoughtful pauses and emotional intelligence, breaking the phrase "he's just... one more" in two, for example.

Clark is an unusual artist, much more so than generally recognized. She makes legit singing acceptable to the masses by minimizing vibrato and adding pop licks on "Don't Cry For Me Argentina," a prime example of her ability to bridge the Broadway and commercial music world.

The show kicks off with Mark Rinzel's rousing version of "Jesus Christ Superstar." Christopher Sloan, does "Close Every Door" from "Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat" and holds the audience spellbound with his strong, searching delivery.

"Starlight Express" is energetically dramatized by Nick Sattinger and Neil Michaels. Michaels then returns like a singing Elmer Gantry with his thunderous gospel rendition of "There's a Light at the End of the Tunnel," another "Starlight Express" number which proves memorable music can come from mediocre shows.

Inevitably, Clark gets to "Memory," the only tune of the evening that feels overly familiar -- it's more fun to watch Sattinger wail out "Mr. Mistoffelees" from "Cats." Toward the show's conclusion, Clark takes over as a star and offers heartfelt performances of "The Perfect Year" and "With One Look."

Brian W. Tidwell, music director and conductor, makes sure that his 28-piece orchestra, the Philharmonica Europa, never overwhelms the singers yet shines through every selection.

Presented by the Pasadena Civic Auditorium Foundation. Directed and choreographed by Arlene Phillips. Lighting, Vivien Leone; musical director, Brian W. Tidwell; sound design, Mark Norfolk.

The Music of Andrew Lloyd Webber (The Pasadena Civic; 3,000 seats; $55 top). Starring: Petula Clark; singers, Jason Burke, Tara Lynn Cotty, Michele Marin, Fabiola Reis, Nick Sattinger, Kristen R. Butcher, Erin Davie, Neil Michaels, Mark Rinzel, Tangena Church, Stephanie Garza, Michael Pesce, Brian Charles Rooney, Christopher Sloan. Opened and reviewed Nov. 14, 2000; closes Nov. 19.

November 15, 2000

by DARYL H. MILLER

The Music of Andrew Lloyd Webber

Petula Clark may be what gets people in the door for another listen to "The Music of Andrew Lloyd Webber," but once there, they'll find much more.

This touring concert show--which has passed through the area before with Sarah Brightman and Michael Crawford--comes with no set design to speak of, and a minimum of choreography or other musical staging. Yet, happily, this ends up focusing attention on the music itself, in electric performances by the regular cast of 12 singer-dancers, as well as Clark, recent headliner in a "Sunset Boulevard" tour, who joined the show last week in San Diego and continues, through Sunday, at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium.

Unlike many musical revues, which lift songs out of shows and attempt to present them in new contexts, this more straightforward concert format presents 20 Lloyd Webber songs in blocks of two or three numbers from each musical, often introduced by an overture. Left in their original settings, the songs retain their meaning and power, and as accompanied by the the 28-piece Philharmonia Europa, with a hint of electric guitar among the highfalutin strings and other orchestral instruments, the compositions reveal a strong classical influence that isn't always evident when listeners are distracted by crashing chandeliers or levitating Sunset Boulevard mansions.

The songs are presented pretty much in chronological order, from the more obviously rock-influenced "Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat" and "Jesus Christ Superstar" of the late '60s/early '70s, through the more operatic "Phantom of the Opera" and "Sunset Boulevard" of the '80s and '90s. This edition also includes the title number from the late-'90s "Whistle Down the Wind," though nothing from Lloyd Webber's newest, "The Beautiful Game."

Clark, whose recording of "Downtown" made such a strong impression in the '60s, takes a daring approach to many of her solos, breaking phrases in unusual places, speaking key words and throwing in little pop trills. What's more, she acts each number with as much commitment as if she were performing in a full production of each show.

Though her first solos came out a bit strangled at Tuesday's opening, her voice warmed throughout the performance, and at the end of the first half, she delivered what was, arguably, her strongest number: "Don't Cry for Me Argentina," from "Evita." The song is Evita's balcony speech to throngs of Argentinians, and Clark freely spoke its most impassioned lines, including a simple, declarative "I love you" that would have made just about anyone take up the crowd's call of "Evi-i-i-ta, Evi-i-i-ta."

Clark's second-half performances of Norma Desmond's songs from "Sunset Boulevard" were filled with all the truth and fragile grace she brought to last year's local performances of the musical, from the calculated flirtatiousness and gaiety of "The Perfect Year" to the breathless wonder of "As If We Never Said Goodbye."

As company members took turns singing the concert's other big solos, they usually proved to be Clark's equals. Mark Rinzel sent a jolt of pure electricity through the auditorium as he growled and screamed through rock-star renditions of the "Jesus Christ Superstar" title song and Jesus' defiant cry to the heavens in "Gethsemane." And, ripping a page from the Michael Crawford songbook, Brian Charles Rooney sang "Phantom's" "Music of the Night" with the sort of whispered bel canto that made Crawford's performance so hypnotizing.

Rock N' Roll Hall of Fame

Cleveland, Ohio USA

HOLIDAY GALA 2000:

HONORING LEGENDARY LADIES OF FILM MUSICALS

Petula was honored along with Jane Russell, Jane Powell, Celeste Holm, Anne Jeffreys, Ann Blyth and Rhonda Fleming. Film clips saluting Petula's work in "Finian's Rainbow" and "Goodbye Mr. Chips" were shown. A concert followed the awards segment and Petula performed 4 songs -- "Downtown", "Don't Sleep in the Subway", "You and I" and dueted with Michael McDonald on "I Couldn't Live Without Your Love".

Rock N' Roll Hall of Fame

Cleveland, Ohio USA

HOLIDAY GALA 2000:

HONORING LEGENDARY LADIES OF FILM MUSICALS

Petula was honored along with Jane Russell, Jane Powell, Celeste Holm, Anne Jeffreys, Ann Blyth and Rhonda Fleming. Film clips saluting Petula's work in "Finian's Rainbow" and "Goodbye Mr. Chips" were shown. A concert followed the awards segment and Petula performed 4 songs -- "Downtown", "Don't Sleep in the Subway", "You and I" and dueted with Michael McDonald on "I Couldn't Live Without Your Love".

Gala to honor musical

sensations from six decades of Hollywood films

Saturday, December 09, 2000

By CLINT O'CONNOR

PLAIN DEALER REPORTER

Saturday, December 09, 2000

By CLINT O'CONNOR

PLAIN DEALER REPORTER

Long before she was sliced and diced in the most famous shower scene in mo tion picture history, Janet Leigh was bopping and stomp ing in Hollywood musicals. Although she was not trained as a dancer, Leigh found herself hoof ing through "Two Tickets to Broad way," "My Sister Eileen," and "Pete Kelly's Blues" among others.

"I wasn't a dancer; I was an actress who could move pretty well," says Leigh, remembered by millions for her bathroom murder in the film "Psycho." "The great thing about those musicals was that we had so much rehearsal time, long before shooting started. You grew very close. You really became like a family. Being an only child, that meant a lot to me."

Leigh and seven other actress-singer-dancers - Jane Russell, Jane Powell, Celeste Holm, Anne Jeffreys, Ann Blyth, Rhonda Fleming and Petula Clark - will be honored tonight at a fund-raiser for Cleveland's Center for Families and Children.

The sold-out event, "Holiday Gala 2000: Honoring Legendary Ladies of Film Musicals," begins at 7 at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, and features performances by Michael McDonald, Gloria Gaynor and other singers.

Leigh, who travels the country for various charities and speaks on behalf of the Library of Congress and American Movie Classics, said "it's kind of nice to be recognized for the musicals for a change, instead of talking about horror."

In addition to musicals and comedies, Leigh has appeared in several heavyweight dramas including Orson Welles' "Touch of Evil," John Frankenheimer's "The Manchurian Candidate," and has starred opposite several A-list actors: Gary Cooper, Errol Flynn, Jimmy Stewart, Paul Newman and her former husband Tony Curtis.

On the phone from her home in Beverly Hills, where she lives with her husband, Robert Brandt, a stockbroker, Leigh says she does not mind being eternally attached to Alfred Hitchcock and the famous shower. "I'm honored. We spend most of our lives trying to create memorable images. To see that film stand the test of time, I'm very flattered."

These days Leigh is working on a novel, her fourth book, and spending time with her daughters, actresses Jamie Lee Curtis and Kelly Curtis, and two grandchildren. And, she says, she is endlessly answering questions about her former colleagues for a flood of TV documentaries. "Between Lifetime, Turner, AMC, the BBC - they've all been here," she says. "It's practically all I do."

Looking back at the best The memorable images of Leigh's fellow honorees reach across six decades of cinema. Jeffreys started her career in 1942, appearing in no fewer than eight films, including "I Married an Angel," the Rodgers and Hart musical that starred Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy.

Blyth hit the screen in 1944, in four films, including "Babes on Swing Street," and "Bowery to Broadway." Rhonda Fleming evolved from playing bit parts to a major role in 1949, co-starring with Bing Crosby in the musical "A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court." Fleming's striking hair was integrated into her movie titles, such as "Those Redheads From Seattle," and "The Redhead and the Cowboy." She didn't play the cowboy. The other honorees:

Russell won fame in 1943 in "The Outlaw," remembered for being sexy, scandalous and directed by one of the true odd geniuses of the century, Howard Hughes. Russell went on to star with Bob Hope in the comedy-western "The Paleface," and in the rollicking musical "Gentlemen Prefer Blondes," with Marilyn Monroe.

Holm's resume reads like a banquet of break-through films. From "Gentleman's Agreement," which explored anti-Semitism, to "The Snake Pit," which examined mental illness - both dangerous topics in late-'40s Hollywood - to the multiple-Oscar-winning "All About Eve." Holm, who won a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for "Gentleman's Agreement," left Hollywood for Broadway in 1950, but returned in the mid-'50s in two musicals, "The Tender Trap" and "High Society," both with Frank Sinatra.

Powell, "the girl next door," who performed on radio and the stage before coming to Hollywood, sang and danced in a slew of musicals in the '40s and '50s. Powell starred with Fred Astaire in Stanley Donen's "Royal Wedding," and was the lead bride in another huge Donen musical, "Seven Brides For Seven Brothers."

Clark is best remembered as the female singing sensation of the '60s, with hits such as "Downtown" and "Don't Sleep in the Subway." But she started acting in films in England as a teenager following World War II. She also starred in two movies in the late '60s: the musical version of "Goodbye, Mr. Chips," with Peter O'Toole, and the musical fantasy "Finian's Rainbow," notable for its co-star (Fred Astaire), its subject matter (racial equality), and its director (Francis Ford Coppola).

The Center for Families and Children is also recognizing the eight women for their contributions to humanitarian causes through the years. The center hopes to raise more than $100,000 for its various causes.

Leigh, who is coming to Cleveland with her daughter Kelly, is firmly committed to the evening's cause.

So many families have been disrupted, with the children cast aside like driftwood," she says. "We need to raise awareness. When they put the word out that they need help for these kinds of events, I'm there."

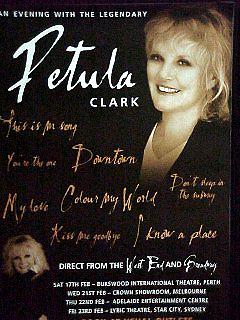

2001

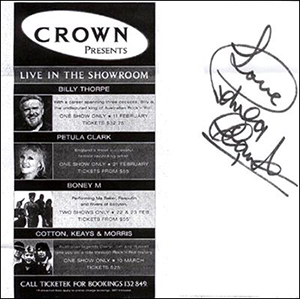

- 17 February, 2001

- 21 February, 2001

- 22 February, 2001

- 23 February, 2001

- 24 February, 2001

- Burswood Theatre, Perth, AUSTRALIA

- Crown Entertainment Centre, Melbourne AUSTRALIA

- Adelaide Entertainment Centre, Adelaide AUSTRALIA

- Star City Lyric Theatre, Sydney, AUSTRALIA

- Twin Towns, Coolangatta-Tweed Heads, AUSTRALIA

- 17 February, 2001

- 21 February, 2001

- 22 February, 2001

- 23 February, 2001

- 24 February, 2001

- Burswood Theatre, Perth, AUSTRALIA

- Crown Entertainment Centre, Melbourne AUSTRALIA

- Adelaide Entertainment Centre, Adelaide AUSTRALIA

- Star City Lyric Theatre, Sydney, AUSTRALIA

- Twin Towns, Coolangatta-Tweed Heads, AUSTRALIA

Songs Performed:

- Sign Of The Times

- Here We Are

- Colour My World

- I'm Not Afraid (A Show Stopper)!!

- Memory

- Look To The Rainbow

- How Are Things In Glocca Morra

- You And I

- Losing My Mind

- Mon Couer Qui Bat

- Kiss Me Goodbye

- Don't Sleep In The Subway INTERMISSION

- Jazz Medley

- I Concentrate On You

- I Never Do Anything Twice

- I Couldnt Live Without Your Love

- The Other Man's Grass Is Always Greener

- This Is My Song

- Tell Me Its Not True

- With One Look

- Theatre Poem

- My Love

- Downtown

Encores

- Here For You

- I Know A Place

Press

Perth

Sign of the Times

Here We Are

Colour My World

I'm Not Afraid

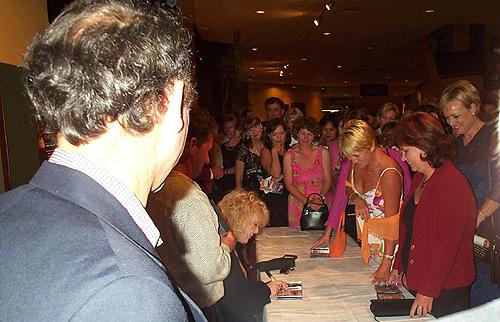

After the show - on the way to sign CD's in the foyer approximately 300 - 400 waiting.

Signing copies of Legendary for fans.

All photos by Vicki Wilkinson

Melbourne

Luckman Fine Arts Center

Los Angeles, California USA

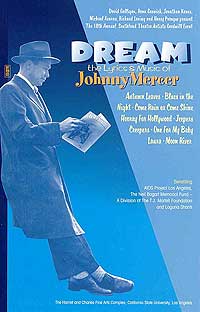

DREAM - THE SONGS OF JOHNNY MERCER - S.T.A.G.E. BENEFIT

PETULA CLARK, Rod McKuen, Margaret Whiting, Carol Cooke, Loretta Devine, Betty Garrett, Tyne Daly, Linda Purl, Sam Harris, Nancy Dussault, Franc D'Ambrosio, Davis Gaines, Jason Graae, Linda Michele, Sally Struthers, Bill Hutton, Jodi Stevens, Greg Poland and Kevin Chamberlin

Luckman Fine Arts Center

Los Angeles, California USA

DREAM - THE SONGS OF JOHNNY MERCER - S.T.A.G.E. BENEFIT PETULA CLARK, Rod McKuen, Margaret Whiting, Carol Cooke, Loretta Devine, Betty Garrett, Tyne Daly, Linda Purl, Sam Harris, Nancy Dussault, Franc D'Ambrosio, Davis Gaines, Jason Graae, Linda Michele, Sally Struthers, Bill Hutton, Jodi Stevens, Greg Poland and Kevin Chamberlin

"Look, look, look to the rainbow. . ."

A Sign of the Times

Chrysler HallMay 20 - 21, 2001

Richard Carpenter

Benoit Martel, Julie Leblanc Vincent Potel, Julie St. Georges

Lou Rawls

All photos by Laurie Parsons Zenobio, except as noted.

"I Couldn't Live Without Your Love"

Photo by Wendy Coffin

Greeting fans outside the stage door.

Photos by Wendy Coffin

Songs Performed:

- Sign of the Times

- Here We Are

- Colour My World

- Don't Sleep in the Subway

- This is My Song

- Look to the Rainbow

- You and I

- I Know a Place

- I Never Do Anything Twice

- I Know a Place

- Tell Me It's Not True (from Blood Brothers)

- With One Look (from Sunset Boulevard)

- My Love / Downtown

- Here for You

Encore:

- I Couldn't Live Without Your Love

Photo by Joy Bolender

Photos by Deb Powers

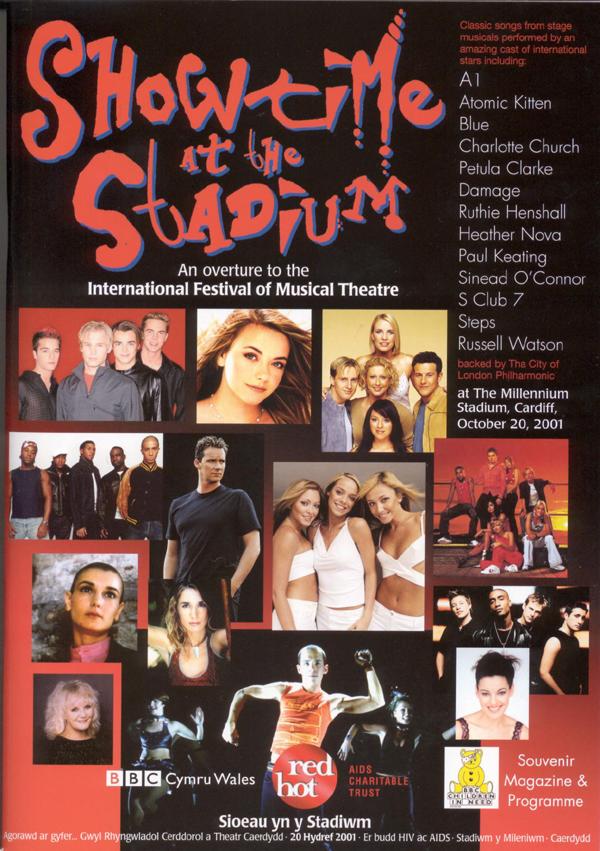

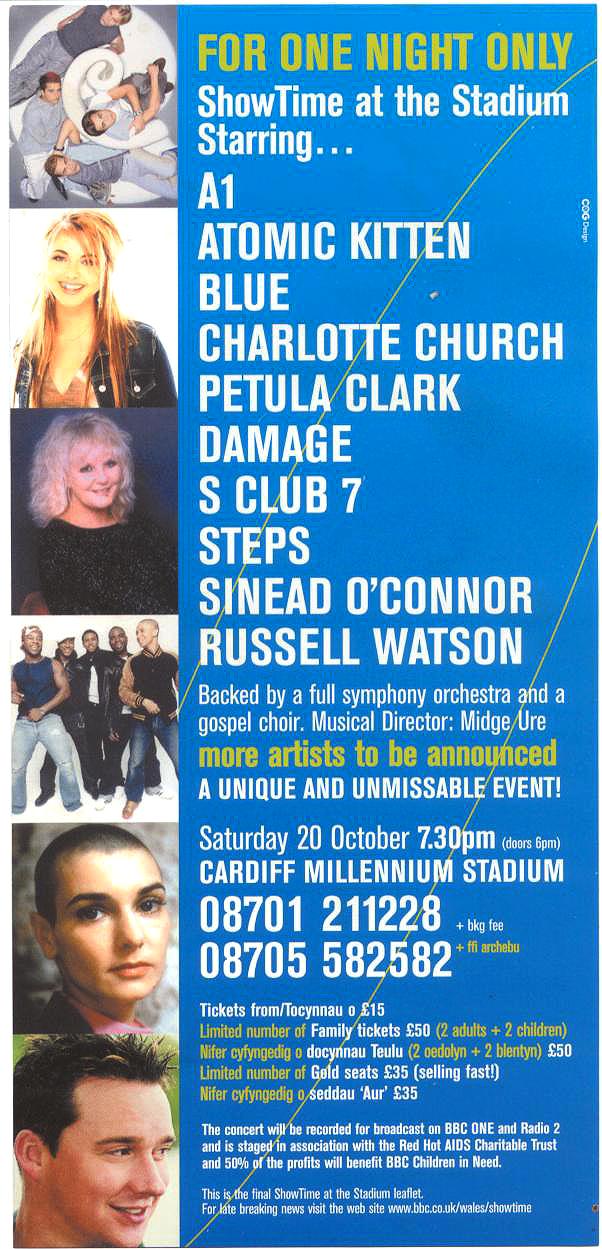

Showtime at the Stadium

20 October, 2001

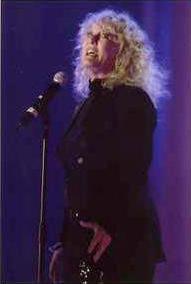

Petula performed "Tell Me It's Not True" from BLOOD BROTHERS, "With One Look" from SUNSET BOULEVARD and then joined Charlotte Church and the entire cast in the chorus of "You'll Never Walk Alone" from CAROUSEL. As she left the stage after "With One Look," the master of ceremonies exclaimed, "Petula Clark, showing us once more what a great star can do."

© photo by Robert Faust

© photo by Robert Faust

SHOWTIME AT THE STADIUM

Petula Clark takes part in a unique charity event at the Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, on October 20, 2001

"Something's coming, something good..." Stephen Sondheim

Atomic Kitten, Midge Ure, Petula, Charlotte Church, Jean Simmons

Atomic Kitten, Midge Ure, Petula, Charlotte Church, Jean Simmons

Some of the world's top musical acts will be appearing at the Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, on October 20 in a spectacular concert celebrating songs from hit musicals.

The concert will be recorded by BBC Wales to be shown on BBC One later in the year. The event is being staged in association with the Red Hot AIDS Charitable Trust.

ShowTime at The Stadium will feature contemporary artists performing classic songs from stage musicals - from West Side Story to Rent - under the guidance of Musical Director Midge Ure. The event will launch the International Festival of Musical Theatre, which will take place in Cardiff every two years from October 2002.

The show will be directed by international stage producer Francesca Zambello and artists will be backed by a 60-piece orchestra and a gospel choir. The participation of local schools and drama colleges will make the concert a truly community event.

Artists already confirmed to perform cover the entire spectrum of music from Petula Clark to Charlotte Church, with many more soon to be announced. So far, Petula is keeping secret the choice of songs she is working on.

Sets from famous musicals currently playing in London's West End and Broadway will also be featured in the spectacular.

Launching the concert Musical Director, Midge Ure said: "Although this is not Live Aid II, the thoughts, compassion and messages are very similar. Music is a great leveller that transcends religion, colour, sex and political systems. ShowTime at The Stadium is a fantastic project to be involved with and I was delighted when asked. I jumped at the chance!".

Jean Simmons, legendary actress and Patron of the Red Hot AIDS Charitable Trust, said: "It gives me great pleasure to be part of ShowTime at The Stadium where many great artists will be performing in this superb stadium in October to raise much needed funding for the global struggle against HIV and AIDS."

David Jackson, Head of Music at BBC Wales says: BBC Wales is delighted to be broadcasting this unique event for BBC One viewers. ShowTime will also be broadcast on BBC Radio2 and Radio1.

TICKETS FOR SHOWTIME AT THE STADIUM ARE AVAILABLE FROM THE MILLENNIUM STADIUM BOX OFFICE PRICED BETWEEN £15 and £35 ON 0870 1211228 or 0870 5582582

--Terry Young -- 20/8/01

The concert will be recorded by BBC Wales to be shown on BBC One later in the year. The event is being staged in association with the Red Hot AIDS Charitable Trust.

ShowTime at The Stadium will feature contemporary artists performing classic songs from stage musicals - from West Side Story to Rent - under the guidance of Musical Director Midge Ure. The event will launch the International Festival of Musical Theatre, which will take place in Cardiff every two years from October 2002.

The show will be directed by international stage producer Francesca Zambello and artists will be backed by a 60-piece orchestra and a gospel choir. The participation of local schools and drama colleges will make the concert a truly community event.

Artists already confirmed to perform cover the entire spectrum of music from Petula Clark to Charlotte Church, with many more soon to be announced. So far, Petula is keeping secret the choice of songs she is working on.

Sets from famous musicals currently playing in London's West End and Broadway will also be featured in the spectacular.

Launching the concert Musical Director, Midge Ure said: "Although this is not Live Aid II, the thoughts, compassion and messages are very similar. Music is a great leveller that transcends religion, colour, sex and political systems. ShowTime at The Stadium is a fantastic project to be involved with and I was delighted when asked. I jumped at the chance!".

Jean Simmons, legendary actress and Patron of the Red Hot AIDS Charitable Trust, said: "It gives me great pleasure to be part of ShowTime at The Stadium where many great artists will be performing in this superb stadium in October to raise much needed funding for the global struggle against HIV and AIDS."

David Jackson, Head of Music at BBC Wales says: BBC Wales is delighted to be broadcasting this unique event for BBC One viewers. ShowTime will also be broadcast on BBC Radio2 and Radio1.

TICKETS FOR SHOWTIME AT THE STADIUM ARE AVAILABLE FROM THE MILLENNIUM STADIUM BOX OFFICE PRICED BETWEEN £15 and £35 ON 0870 1211228 or 0870 5582582

--Terry Young -- 20/8/01

Petula performed:

- I Couldn't Live Without Your Love

- This is My Song (French/English)

- Coeur Blessé

- My Love / Downtown

- Kiss Me Goodbye

DIAMOND AWARDS FESTIVAL

GEORGE BAKER SELECTION

GEORGE BAKER SELECTION

-

Dear Ann

I'm On My Way

Sing A Song Of Love

Una Paloma Blanca

Morning Sky

Little Green Bag

-

The Letter

Cry Like A Baby

Choo Choo Train

-

With All My Heart

Baby Lover

Romeo

Chariot

Coeur Blessé

Downtown

C'est Ma Chanson

-

In The Summertime

Maggie

Mungo Blues

Alright Alright Alright

-

I'll Go Where Your Music Takes Me

Now Is The Time

Do The Funky Conga

-

Eenzaam Zonder Jou

Hoop Doet Leven

Hemelsblauw

Ik Ben Vrij (I Will Survive)

-

Always The Last

What If I

Holidays

Je T'Aime À Mourir

-

Clair

Get Down

Nothing Rhymed

O-Oh Baby

Matrimony

2002

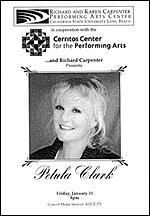

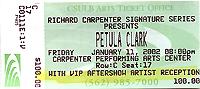

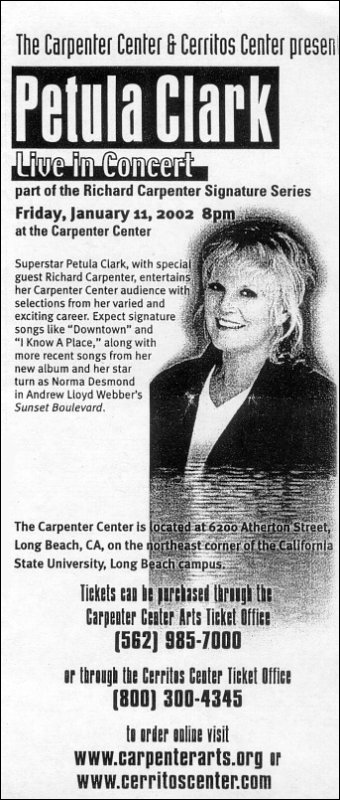

Richard & Karen Carpenter Performing Arts Center

©Photos by Pat Fox

Songs Performed:

- Sign of the Times

- Here We Are

- Colour My World

- I'm Not Afraid

- Don't Sleep in the Subway

- This Is My Song

- Look to the Rainbow

- How Are Things in Gloccamorra

- You and I

- La Vie En Rose (with Petula at the piano)

- I Know a Place

- Kiss Me Goodbye

- Tell Me It"s Not True

- Jazz Medley:

If I Had You/Petula's jazz rap/Just You, Just Me - The Other Man's Grass Is Always Greener

- I Need to Be in Love (with Richard Carpenter)

- All Those Years Ago (with Richard Carpenter)

- Losing My Mind

- I Never Do Anything Twice

- With One Look

- It's a Funny Thing, the Theatre (the poem)

- My Love / Downtown

- Here for You (with Petula at the piano)

Photos by Pat Mann

Photos by Pat Mann

Photos by Rich Tanguy

Photos by Rich Tanguy

©Photos by David Van Densen

©Photos by David Van Densen

©Photo by Bob Slavin

©Photo by Bob Slavin

Petula and Richard with Executive Committee Member Ron Zurek of the Carpenter Center for the Performing Arts. L to R: Kevin Donnelly, Sylvia Donnelly, Richard, Petula, Ron Zurek, Julie Zurek

Photo: Ron Zurek

- 11 May, 2002

- 12 May, 2002

- 15 May, 2002

- 16 May, 2002

- 17 May, 2002

- 18 May, 2002

- 19 May, 2002

- 23 May, 2002

- 24 May, 2002

- 26 May, 2002

- 28 May, 2002

- 29 May, 2002

- 30 May, 2002

- 31 May, 2002

- 1 June, 2002

- 5 June, 2002

- 6 June, 2002

- 7 June, 2002

- 8 June, 2002

- 9 June, 2002

- 11 June, 2002

- 12 June, 2002

- 13 June, 2002

- 14 June, 2002

- Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool, England UK

- New Victoria Theatre, Woking, England UK

- Victoria Hall, Stoke-on-Trent, England UK

- His Majesty's Theatre, Aberdeen, Scotland UK

- Festival Theatre, Edinburgh, Scotland UK

- Royal Concert Hall, Glasgow, Scotland UK

- Opera House, Newcastle, England UK

- Pavilion Theatre, Bournemouth, England UK

- Derngate Theatre, Northampton, England UK

- Palladium, London, England UK

- Cliff's Pavillion, Southend, England UK

- The Orchard, Dartford, England

- De Montfort Hall, Leicester, England, UK

- Grand Opera House, York, England UK

- Fairfield Hall, Croydon, England UK

- Congress Theatre, Eastbourne, England UK

- Bridgewater Hall, Manchester, England UK

- Hexagon Theatre, Reading, England UK

- Royal Concert Hall, Nottingham, England UK

- Symphony Hall, Birmingham, England UK

- National Concert Hall, Dublin, Ireland, UK

- Waterfront Hall, Belfast Northern Ireland, UK

- Millennium Forum, Derry, Northern Ireland, UK

- St. George's Hall, Bradford, England, UK

- 11 May, 2002

- 12 May, 2002

- 15 May, 2002

- 16 May, 2002

- 17 May, 2002

- 18 May, 2002

- 19 May, 2002

- 23 May, 2002

- 24 May, 2002

- 26 May, 2002

- 28 May, 2002

- 29 May, 2002

- 30 May, 2002

- 31 May, 2002

- 1 June, 2002

- 5 June, 2002

- 6 June, 2002

- 7 June, 2002

- 8 June, 2002

- 9 June, 2002

- 11 June, 2002

- 12 June, 2002

- 13 June, 2002

- 14 June, 2002

- Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool, England UK

- New Victoria Theatre, Woking, England UK

- Victoria Hall, Stoke-on-Trent, England UK

- His Majesty's Theatre, Aberdeen, Scotland UK

- Festival Theatre, Edinburgh, Scotland UK

- Royal Concert Hall, Glasgow, Scotland UK

- Opera House, Newcastle, England UK

- Pavilion Theatre, Bournemouth, England UK

- Derngate Theatre, Northampton, England UK

- Palladium, London, England UK

- Cliff's Pavillion, Southend, England UK

- The Orchard, Dartford, England

- De Montfort Hall, Leicester, England, UK

- Grand Opera House, York, England UK

- Fairfield Hall, Croydon, England UK

- Congress Theatre, Eastbourne, England UK

- Bridgewater Hall, Manchester, England UK

- Hexagon Theatre, Reading, England UK

- Royal Concert Hall, Nottingham, England UK

- Symphony Hall, Birmingham, England UK

- National Concert Hall, Dublin, Ireland, UK

- Waterfront Hall, Belfast Northern Ireland, UK

- Millennium Forum, Derry, Northern Ireland, UK

- St. George's Hall, Bradford, England, UK

Pride Weekend

in

Brighton & Hove

Saturday, 10 August, 2002 "The heavens opened, the rain came down and a thunderstorm turned Preston Park into a mudbath. But nothing could wash out Britain's biggest free gay celebration."

This is Brighton & Hove

I Know a Place

I Know a Place

Don't Sleep in the Subway

Don't Sleep in the Subway Memories of Love

Memories of LovePhotos by Mike Jones & Martin Wilson

Downtown

Downtown

Patula and fan Martin Wilson

Patula and fan Martin Wilson

Downtown

Downtown Patula and fan Martin Wilson

Patula and fan Martin Wilson I Couldn't Live Without Your Love

I Couldn't Live Without Your Love2003

The Regent Wall Street Hotel

New York, New York USA

Wall Street Rising

First Annual Leadership Awards in New York City. Twice interrupted by applause for her performance of "Downtown", Petula also debuted "Starting All Over Again", her tribute song to September 11th, which was met with a very emotional response from the attendees

The Regent Wall Street Hotel

New York, New York USA

Wall Street Rising

First Annual Leadership Awards in New York City. Twice interrupted by applause for her performance of "Downtown", Petula also debuted "Starting All Over Again", her tribute song to September 11th, which was met with a very emotional response from the attendees

Photo by Phil Meehan

Photo by Phil Meehan

Wyvern FM's Classical Picnic & Prom Extravaganza

Sunday, June 1, 2003Worcestershire County Cricket Club

Worcester, England

Dazzling

The festivities continued at the classical event, last night, with Petula Clark giving a dazzling hour-long performance with the English National Orchestra.

The 2,000 strong crowd cheered, danced and waved their Union Jacks and St George flags, as the concert came to a colourful, noisy end with a spectacular firework display.

Conductor Jae Alexander led the orchestra through classic pieces including the March of the Toreadors, the 1812 Overture and The Hornpipe.

Soprano Sarah Ryan gave emotive performances of Rule Britannia, Jerusalem, and Land of Hope and Glory.

. . .The festivities climaxed with a late evening firework display. . .

The festivities continued at the classical event, last night, with Petula Clark giving a dazzling hour-long performance with the English National Orchestra.

The 2,000 strong crowd cheered, danced and waved their Union Jacks and St George flags, as the concert came to a colourful, noisy end with a spectacular firework display.

Conductor Jae Alexander led the orchestra through classic pieces including the March of the Toreadors, the 1812 Overture and The Hornpipe.

Soprano Sarah Ryan gave emotive performances of Rule Britannia, Jerusalem, and Land of Hope and Glory.

. . .The festivities climaxed with a late evening firework display. . .

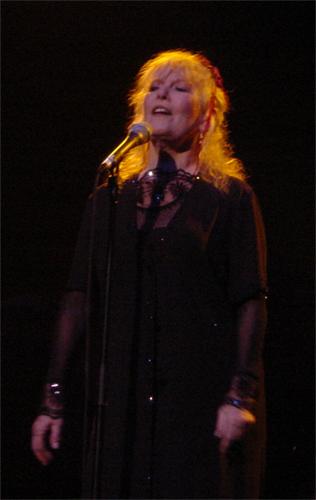

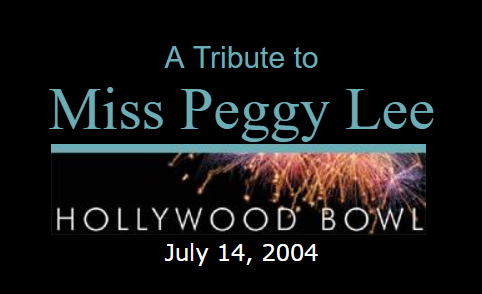

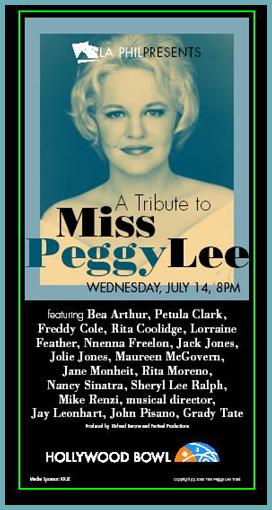

Carnegie HallNew York, New York USA

There'll Be Another Spring: A Tribute to Miss Peggy Lee

Nancy Sinatra, Ann Hampton Calloway, Freddy Cole, Deborah Harry, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Rita Moreno, Chris Connor, Shirley Horn, Peter Cincotti, PETULA CLARK, Maria Muldaur, Eric Comstock, Cy Coleman, Corky Hale, Jackie Cain, Marian McPartland.

Carnegie HallNew York, New York USA

There'll Be Another Spring: A Tribute to Miss Peggy Lee

Nancy Sinatra, Ann Hampton Calloway, Freddy Cole, Deborah Harry, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Rita Moreno, Chris Connor, Shirley Horn, Peter Cincotti, PETULA CLARK, Maria Muldaur, Eric Comstock, Cy Coleman, Corky Hale, Jackie Cain, Marian McPartland.

Left to right: Dee Dee Bridgewater, Chris Connor, Jane Monheit, Deborah Harry, Petula Clark, Ann Hampton Callaway, Maria Muldaur, and Nancy Sinatra.

Photo by Richard Termine

June 25, 2003

June 25, 2003By Frank Scheck

In a stirring example of the sort of show it does best, the JVC Jazz Festival presented this affectionate tribute to one of the most important figures in popular music. "There'll Be Another Spring: A Tribute to Miss Peggy Lee" featured an all-star cast performing songs both associated with and written by the late singer, who performed at the festival in 1995.

Produced by Richard Barone (the former leader of the Bongos, and an interesting choice), the show featured a gallery of Lee's contemporaries as well as younger singers eager to pay their respects. Backed by a small orchestra led by Mike Renzi and anchored by the stalwart rhythm section of Bucky Pizzarelli (guitar), Jay Leonhart (bass) and Grady Tate (drums), the show featured songs from every period in her career, from "Why Don't You Do Right?" -- her first hit with Benny Goodman, here delivered with the proper swagger by Nancy Sinatra -- to the fascinatingly quirky "Is That All There Is?"

After an introduction by Lee's daughter, Nicki Lee Foster, and a video montage depicting the highlights of her career, the well-paced show featured a succession of strong performances: Ann Hampton Calloway delightedly vamped her way through "Manana"; Freddy Cole applied his smooth gravel to "I Don't Know Enough About You"; Rita Moreno sang "Don't Smoke in Bed" with seductive restraint while later dancing and rapping rather incongruously through "New York City Blues"; Dee Dee Bridgewater brought down the house with such Lee signature tunes as "Black Coffee" and the sultry "Fever"; Maria Muldaur, who recently released a Lee tribute album, delivered the bluesy "I'm a Woman" in earthy style; and Petula Clark showed off her still-distinctive pipes with Lee songs like "Things Are Swingin'."

Shirley Horn, performing in a wheelchair, demonstrated her subtle but mesmerizing vocal approach on "The Folks Who Live on the Hill," while Deborah Harry, who by now bears something of a resemblance to Lee, proved that more is less with her physically suggestive, too-effortful take on "Lover." Harry did later acquit herself with an entertaining duet with Sinatra on a medley of songs co-written by Lee for "The Lady and the Tramp." It was introduced by a promotional video featuring Walt Disney, more than a little ironic considering the singer's late- in-life lawsuit against his company.

Such younger performers as Peter Cincotti, infusing "I Love Being Here With You" with his high-spirited swinging, and Jane Monheit, applying her gorgeous vocals to "Sweet Happy Life," demonstrated the continuity of pop traditions. Less successful was singer Eric Comstock, who blandly worked his way through "I'm in Love Again" and "The Shining Sea," though admittedly he was filling in on short notice for an absent Bea Arthur on the latter.

The best moments came from Lee's contemporaries, such as Chris Connor - - who movingly sang "Where Can I Go Without You?" -- and Jackie Cain and Marian McPartland, who duetted on the little-known Lee/McPartland composition "In the Days of Our Love." And composer Cy Coleman, who co- wrote several songs with Lee, delivered several numbers in his less than agile but highly enthusiastic voice.

Wisely, nobody attempted Lee's signature number, "Is That All There Is?" Instead, after an introduction from Mike Stoller, the song's co- writer, a video of Lee herself performing the song was shown. Filing onstage to watch the clip with rapt adoration, the entire ensemble capped off the evening with a touching group rendition of "I'll Be Seeing You."

Produced by Richard Barone (the former leader of the Bongos, and an interesting choice), the show featured a gallery of Lee's contemporaries as well as younger singers eager to pay their respects. Backed by a small orchestra led by Mike Renzi and anchored by the stalwart rhythm section of Bucky Pizzarelli (guitar), Jay Leonhart (bass) and Grady Tate (drums), the show featured songs from every period in her career, from "Why Don't You Do Right?" -- her first hit with Benny Goodman, here delivered with the proper swagger by Nancy Sinatra -- to the fascinatingly quirky "Is That All There Is?"

After an introduction by Lee's daughter, Nicki Lee Foster, and a video montage depicting the highlights of her career, the well-paced show featured a succession of strong performances: Ann Hampton Calloway delightedly vamped her way through "Manana"; Freddy Cole applied his smooth gravel to "I Don't Know Enough About You"; Rita Moreno sang "Don't Smoke in Bed" with seductive restraint while later dancing and rapping rather incongruously through "New York City Blues"; Dee Dee Bridgewater brought down the house with such Lee signature tunes as "Black Coffee" and the sultry "Fever"; Maria Muldaur, who recently released a Lee tribute album, delivered the bluesy "I'm a Woman" in earthy style; and Petula Clark showed off her still-distinctive pipes with Lee songs like "Things Are Swingin'."

Shirley Horn, performing in a wheelchair, demonstrated her subtle but mesmerizing vocal approach on "The Folks Who Live on the Hill," while Deborah Harry, who by now bears something of a resemblance to Lee, proved that more is less with her physically suggestive, too-effortful take on "Lover." Harry did later acquit herself with an entertaining duet with Sinatra on a medley of songs co-written by Lee for "The Lady and the Tramp." It was introduced by a promotional video featuring Walt Disney, more than a little ironic considering the singer's late- in-life lawsuit against his company.

Such younger performers as Peter Cincotti, infusing "I Love Being Here With You" with his high-spirited swinging, and Jane Monheit, applying her gorgeous vocals to "Sweet Happy Life," demonstrated the continuity of pop traditions. Less successful was singer Eric Comstock, who blandly worked his way through "I'm in Love Again" and "The Shining Sea," though admittedly he was filling in on short notice for an absent Bea Arthur on the latter.

The best moments came from Lee's contemporaries, such as Chris Connor - - who movingly sang "Where Can I Go Without You?" -- and Jackie Cain and Marian McPartland, who duetted on the little-known Lee/McPartland composition "In the Days of Our Love." And composer Cy Coleman, who co- wrote several songs with Lee, delivered several numbers in his less than agile but highly enthusiastic voice.

Wisely, nobody attempted Lee's signature number, "Is That All There Is?" Instead, after an introduction from Mike Stoller, the song's co- writer, a video of Lee herself performing the song was shown. Filing onstage to watch the clip with rapt adoration, the entire ensemble capped off the evening with a touching group rendition of "I'll Be Seeing You."

Photos by Laurie Parsons Zenobio

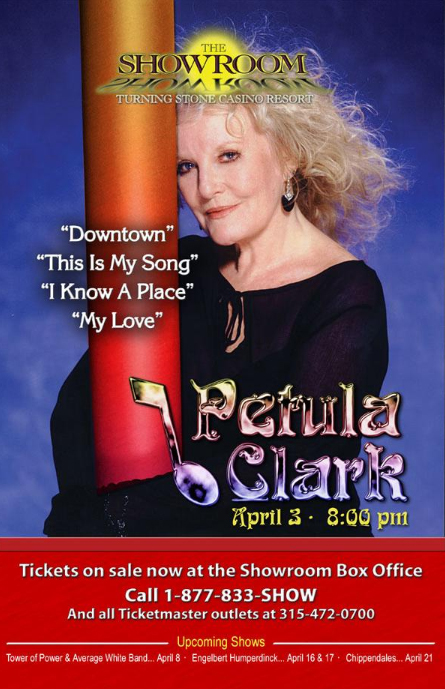

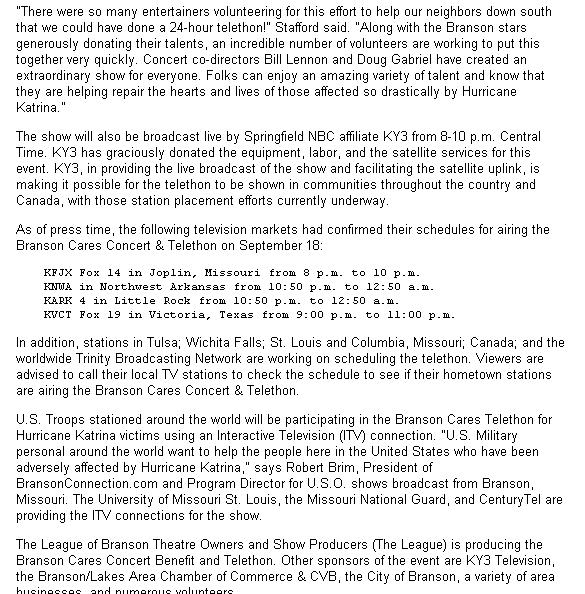

Photos by Laurie Parsons ZenobioSong List

- Who Am I

- Wedding Song

- Don't Sleep in the Subway

- I'm Not Afraid

- This is My Song

- I Know a Place

- Look to the Rainbow

- Sixties Medley

- Tell Me It's Not True

- Jazz Medley

(If I Had You/Just You, Just Me) - Starting All Over Again

- Sign of the Times

- Theatre Poem

- Losing My Mind

- With One Look

- Love Medley

-

Downtown

Encores:

- Here for You

- I Couldn't Live Without Your Love

A view of the crowd.

A view of the crowd.

Admiring a gift from a young fan.

Admiring a gift from a young fan.

Photos by Michael Holmstrom

Photos by Michael Holmstrom

VIVRE photo by Jean-Michel Barrault

VIVRE photo by Jean-Michel Barrault Photo by Pat Fox

Photo by Pat Fox  Photo by Daniel Bédard

Photo by Daniel Bédard

Photo by Pat Fox

Photo by Pat Fox Program note translation:

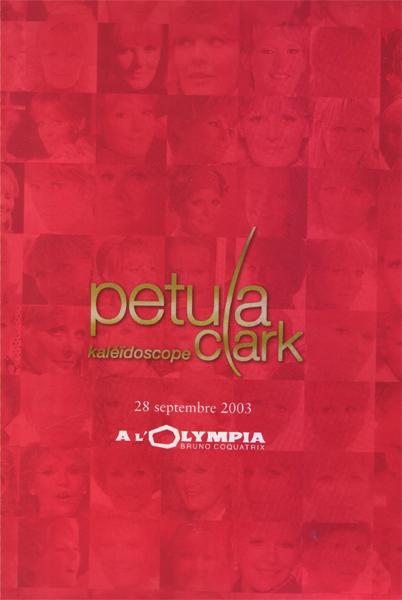

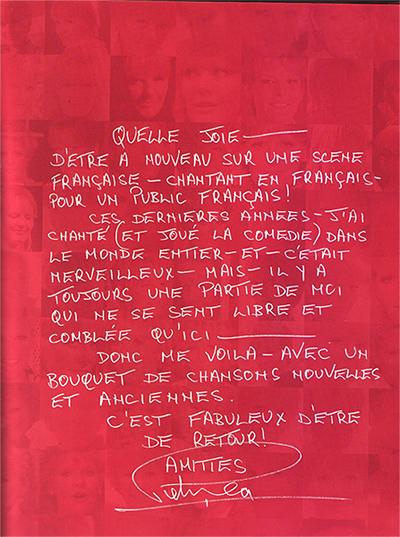

What joy--

to be on a French stage--singing in French--

for a French audience! These last few years I have sung (and starred in plays) throughout the entire world-- and it has been marvelous--but--there has always been a part of me that did not feel free and complete, except here--

So here we are-- with a bouquet of new and old songs

It's fabulous to be back!

Love,

Petula

Photo by Jean-Michel Barrault

Photo by Jean-Michel Barrault

Set 1

- Overture (Recommencer à zèro/Romêo/C'est ma chanson/Que fais-tu là Petula/Chariot)

- Recommencer à zero

- French Medley (Je me sens bien apres de toi - Romeo - Bleu, blanc, rouge - Je me sens bien apres de toi

- I'm Not Afraid

- Nous etions tous des enfants (New piece on her childhood and the early years, based on the one from Montreal, but very different melody

- Un Enfant

- Look to the Rainbow

- You & I

- Que Fais-tu la, Petula?

- SOS Mozart (lovely new Pierre Delanoe song)

- Don't Sleep in the Subway

- Another French medley (Prends Mon Coeur/A London/Marin/Ya Ya Twist/Chariot)

- C'est ma chanson

Set 2

- If I Had You/Just You, Just Me

(rap section in French)

- Coeur Blessé

- Gainsbourg Medley - La Chanson de Gainsbourg/O o Sheriff/ La Gadoue

- La Nuit n'en finit plus

La Nuit n'en finit plus

(who says she never does anything twice?)

- Tell Me it's Not True

- With One Look

- Vivre

- I Know a Place

- Sign of the Times

- Downtown

Encores:

- Here for You (French & English)

- Dis-moi au revoir (Kiss Me Goodbye)

- I Couldn't Live without Your Love

Additional curtain calls followed (she came and went off stage several times, and then had 2 additional curtain calls)

Photo by Jean-Michel Barrault

Photo by Jean-Michel Barrault  Photo by Marie-Jeanne Boyer

Photo by Marie-Jeanne Boyer  Photo by Jérôme Guerin

Photo by Jérôme Guerinjerome.guerin8@wanadoo.fr

Photo by Marie-Jeanne Boyer

Photo by Marie-Jeanne Boyer

©Photos by Grae Leigh

©Photos by Grae Leigh

©Photos by Jean-Michel Barrault

©Photos by Jean-Michel Barrault

Photo by Phil Meehan

Photo by Phil Meehan  ©Photo by Jean-Michel Barrault

©Photo by Jean-Michel Barrault

SUCCESS FOR PETULA'S GAMBLE

There wasn't a single empty seat for Petula Clark at the Olympia late yesterday afternoon. Nostalgia or not, it has to be said that Parisians had not seen her on this legendary stage since April 1965. "I was there and I remember the excitement that her performance created at the time" said Albert, a dashing man in his fifties who was very happy to see the English singer again.

In the interval, this lifelong fan was in seventh heaven. "She has a voice which is unbelievably powerful for a woman of her years, the tone is unimpaired. Obviously, what pleased me was to hear all the old hits like "Que fais-tu la, Petula?", "Chariot" and "C'est ma chanson"....And then I have found songs that hadn't been out before on her new album "Kaleidoscope".

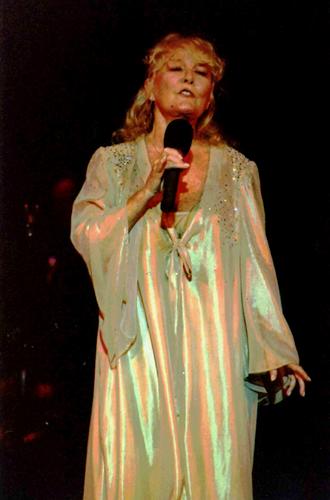

This enthusiasm is totally consistent with the ovation which the singer received when she came on stage at 6p.m. on the dot in a shimmering gold dress: an audience of fans, of course, but also some with an interest arising from hearing her songs on Radio Nostalgie and whom the star was able to win over by confessing to huge nerves before going into "I'm not afraid", the story of how she overcame her natural shyness. Between each song, she told of her contacts with, in particular, Peter O'Toole, Fred Astaire and Charlie Chaplin, with whom she danced at his home in Geneva. In the wings, Petula's husband, Claude Wolff, was heartened: his wife had well and truly pulled off her gamble with the Olympia.

Caption: OLYMPIA, YESTERDAY. Thirty-eight years after leaving them, Petula Clark won Parisians back.

English translation by Peter Marren

There wasn't a single empty seat for Petula Clark at the Olympia late yesterday afternoon. Nostalgia or not, it has to be said that Parisians had not seen her on this legendary stage since April 1965. "I was there and I remember the excitement that her performance created at the time" said Albert, a dashing man in his fifties who was very happy to see the English singer again.

In the interval, this lifelong fan was in seventh heaven. "She has a voice which is unbelievably powerful for a woman of her years, the tone is unimpaired. Obviously, what pleased me was to hear all the old hits like "Que fais-tu la, Petula?", "Chariot" and "C'est ma chanson"....And then I have found songs that hadn't been out before on her new album "Kaleidoscope".

This enthusiasm is totally consistent with the ovation which the singer received when she came on stage at 6p.m. on the dot in a shimmering gold dress: an audience of fans, of course, but also some with an interest arising from hearing her songs on Radio Nostalgie and whom the star was able to win over by confessing to huge nerves before going into "I'm not afraid", the story of how she overcame her natural shyness. Between each song, she told of her contacts with, in particular, Peter O'Toole, Fred Astaire and Charlie Chaplin, with whom she danced at his home in Geneva. In the wings, Petula's husband, Claude Wolff, was heartened: his wife had well and truly pulled off her gamble with the Olympia.

Caption: OLYMPIA, YESTERDAY. Thirty-eight years after leaving them, Petula Clark won Parisians back.

English translation by Peter Marren

© Doug McKenzie Photography

© Doug McKenzie Photography

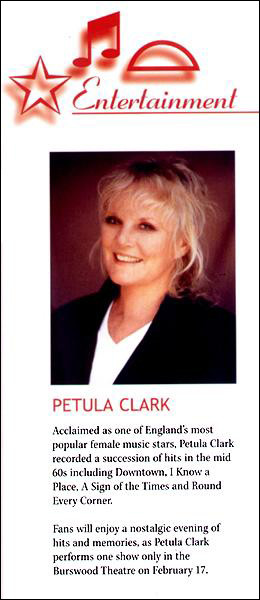

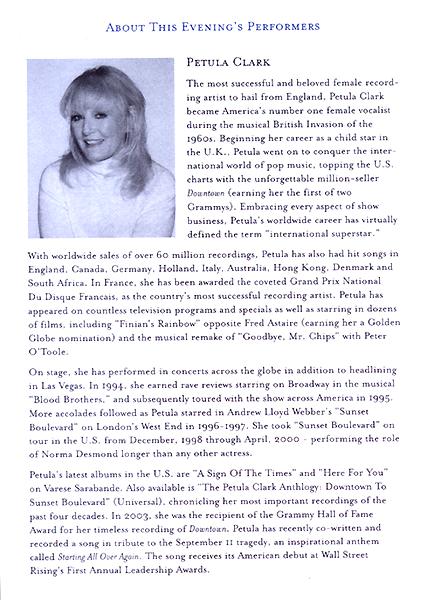

PETULA CLARK'S showbiz career started in the mid 30's and by her eighth birthday the child singer and actress was already a British 'star'. Since those early days she has achieved outstanding success over many years, initially on radio, then in films, then with hit records, then more films plus television, musical theatre, concerts and songwriting.

In June 1954, after starring in a long list of British films, she had her first hit record with "The Little Shoemaker." In the early 60's, whilst enjoying a constant stream of UK successes such as "Sailor" and Romeo" la Petu-la conquered France then swept through other European countries seducing everyone with her irresistable appeal. Late in 1964 her career took a new and vital direction when "Downtown" topped the USA charts, selling more than 3 million singles worldwide, over a million in the States alone. This earned her a coveted Grammy, the first British female singer to win this Award.

Further hit records and popularity in the States found her performing concers in the cities, seasons in the gambling capitals, more films, dozens of television appearances including her own series and specials.

Meanwhile, the rest of the world, especially the UK also wanted Petula and this required astute management and some pretty exhausting travel schedules. Throughout this busy period Pet also managed to raise a family.

Of particular note within an amazing career are her fine stage performances as Maria in "The Sound of Music", Mrs. Johnstone in "Blood Brothers" and for me, the best 'Norma Desmond' of all in "Sunset Boulevard."

2003 and Petula (honoured with a CBE in 1998) continues to fill her life with recording, writing songs, guest appearances, travelling (lots of that) and regularly performing her own wonderful one-woman concerts.

Needless to say, I adore her and I'm forever in her debt for the encouragement and inspiration she gave me.

Tony Hatch

In June 1954, after starring in a long list of British films, she had her first hit record with "The Little Shoemaker." In the early 60's, whilst enjoying a constant stream of UK successes such as "Sailor" and Romeo" la Petu-la conquered France then swept through other European countries seducing everyone with her irresistable appeal. Late in 1964 her career took a new and vital direction when "Downtown" topped the USA charts, selling more than 3 million singles worldwide, over a million in the States alone. This earned her a coveted Grammy, the first British female singer to win this Award.

Further hit records and popularity in the States found her performing concers in the cities, seasons in the gambling capitals, more films, dozens of television appearances including her own series and specials.

Meanwhile, the rest of the world, especially the UK also wanted Petula and this required astute management and some pretty exhausting travel schedules. Throughout this busy period Pet also managed to raise a family.

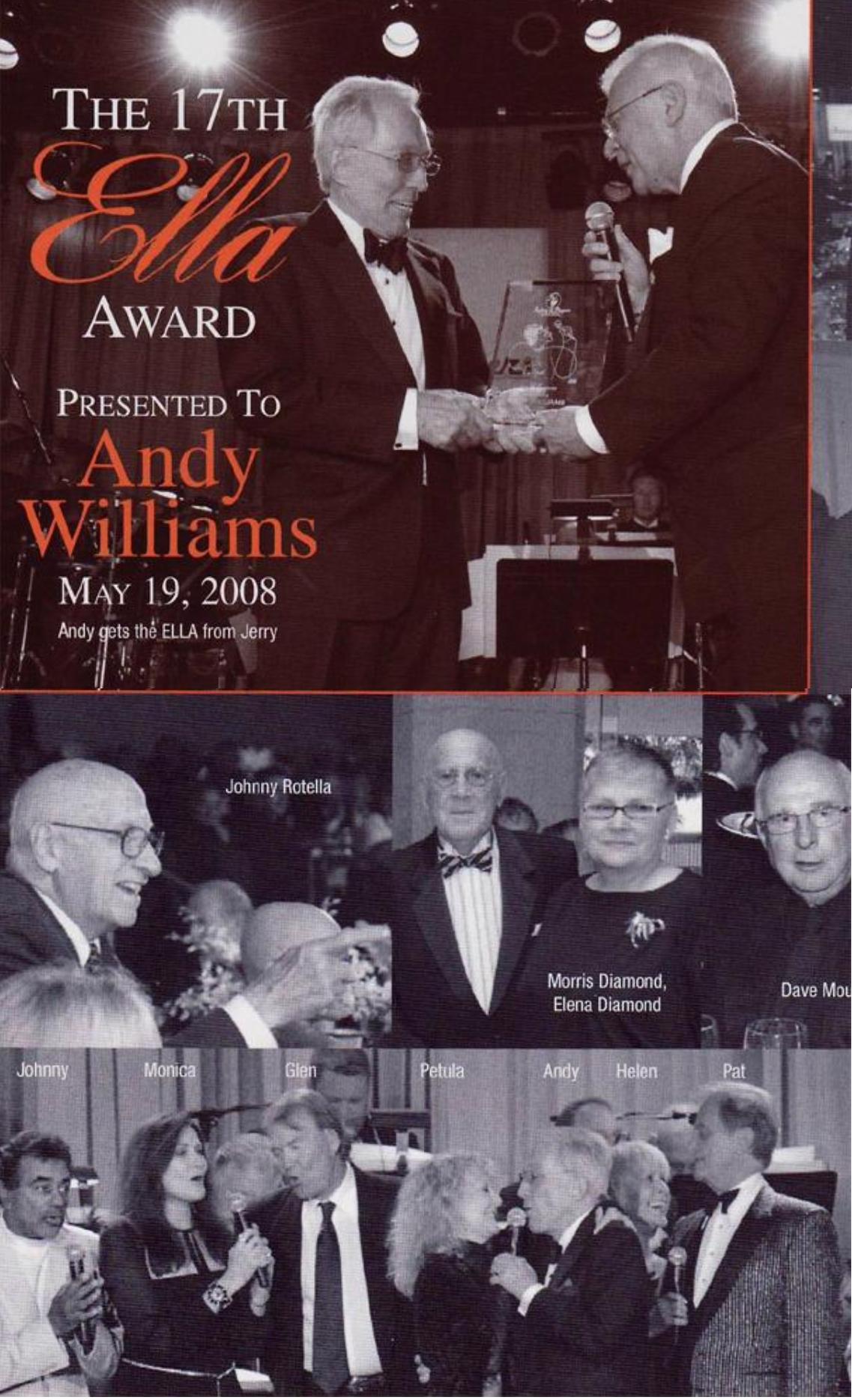

Of particular note within an amazing career are her fine stage performances as Maria in "The Sound of Music", Mrs. Johnstone in "Blood Brothers" and for me, the best 'Norma Desmond' of all in "Sunset Boulevard."